This report is taken from PN Review 281, Volume 51 Number 3, January - February 2025.

Auerbach, 1930-2024Auerbach – Artist, Exemplar

(i.m. 1930–2024)

All my paragons have had clay feet, except Frank Auerbach.

He died last week at the age of ninety-three, universally eulogized as ‘the greatest living artist’1 of his time. ‘With the death of [Francis] Bacon in 1992 and [Lucian] Freud in 2011, he became a leading contender for the unofficial title “greatest living British artist.”’2 “He will be remembered as an […] artist whose contribution to portraiture and landscape painting has had no equal during his long lifetime.”3 From this judgment none dissent.

He was not a world-famous artist in 1994 when I was walking down Albemarle Street towards Piccadilly late on an Indian summer's afternoon and a painting of a head in a gallery window arrested me. Frank Auerbach, the name stencilled on Marlborough Gallery’s window above the painting, was new to me, a recent émigré to London from D.C. and newcomer to the British art world. With a half hour before the gallery closed, I entered.

On the light grey walls inside hung some twenty paintings, mostly portrait size heads (24” x 24”), a few cityscapes twice that size, and several drawings. All the paintings were heavily impasted, the paint almost sculptural, with thick slashes of black and primary colours scarring the canvases. They were indecipherable until I found the right distance from which to view them; even then heads, figures, streets and buildings were barely discernible. Not all had been sold.

But they rooted in my memory. By 1994 Auerbach had been painting and drawing for some forty-five years. A succès d’estime in Britain almost from the first, the London art world – artists, critics, scholars, major collectors – over time increasingly lauded him. Among fellow figurative artists, dubbed the School of London – Michael Andrews, Bacon, Freud, R.B. Kitaj, Leon Kossoff – he was legendary: for his sad childhood, his work habits, above all his artistic practice. He was the only contemporary Lucian Freud collected in depth.

Auerbach’s Jewish parents dispatched him, alone, to Britain from Berlin as an eight-year-old refugee in 1938. There for ten years he boarded at Bunce Court, a progressive Quaker school in Kent. The Germans had murdered his parents somewhere in the camps by the end of 1942, leaving Gerda Boehm, a much older cousin in North London, his only living relative.

By the time he graduated from the Royal College of Art in 1955 he had developed the fundamentals of his impasted, compulsively reworked, almost abstract style of figuration. He had a small circle of sitters, and a few cityscapes, that he drew and painted repeatedly his whole career. Every morning he scraped off or erased what he had painted or drawn the night before, time and again, till the image embodied what he called the ‘raw truth’. With paintings this reworking might build up a thick base you could carve with a palette knife; with drawings it often wore holes in the paper he then patched. Both methods created palimpsests one sensed beneath the final image. Such was his style from his debut show at London’s Beaux Arts Gallery in 1956 until his death sixty-eight years later.

More than his craft was sui generis. He painted 364 days a year, taking off only Christmas Day. For thirty-three years he lived seven days a week in his one room studio in Camden’s Mornington Crescent area; from 1987 until his death he lived there three. Until his last decade he almost invariably refused interviews. Openings, his own included, he gave a miss, likewise dinner parties. He refused a knighthood; after his fame escaped gravity he declined to become a Companion of Honour, explaining that it would have been a distraction, bringing with it unwanted personal attention.

I knew none of this, nor had I met him, when I bought his Head of Gerda Boehm (1978–9) at auction in 1996. Sotheby’s put it in a ‘Day Sale’ at which they offer less expensive art than in their evening sales. His paintings which had haunted me since I first saw them at Marlborough came clearly to mind when I saw the Gerda Boehm image in Sotheby’s catalogue. But the Gerda Boehm was even more striking than the paintings I remembered, its guide price a third less. I readied my paddle.

Ever since, the Head of Gerda Boehm has hung four feet to the right of my desk. For near three decades I’ve looked at it every day when I sit down to work. When my eyes lift from my laptop I often swivel to Gerda Boehm; never does she age or stale, the hallmark of great art.

During my first decade in London, lawyering and a long-standing interest in art conjoined to involve me deeply in the British art world. I met Kitaj, Paula Rego and Anish Kapoor amongst other noted British artists. But it was to Auerbach I returned most often.

I grew familiar with his oeuvre from seeing it in exhibitions and catalogues. The essays in them, as well as reviews, monographs and occasional interviews taught me about his style, habits and aesthetic aims. From his sitters, dealers, curators, scholars I learned of the physical labour that making his art required, his erudition and his love of poetry. And from all these sources, especially interviews in his last decade, shone his extraordinary articulateness, thoughtfulness and profound understanding of his craft.

Frank Auerbach was no curmudgeonly recluse, no anchorite. Obsession had no purchase on his character. Warm, friendly, a wonderful dinner companion, dedicated. He chose not to travel or socialize because, as he said in one late interview, when he got up in the morning he could think of nothing better to do than paint, and so he did.

Fame did not change him. He had no ‘side’, never denigrating other artists, sympathetic to poor sinners who must paint for their dinners, to those whose careers never caught fire. He visited museums and galleries at times when there were few other visitors or none, the better to study the art displayed. An artist I knew ran into him more than once at these shows, as did I at the Royal Academy’s Hockney Exhibition in May 2017.

Frank and Julia Auerbach at David Hockney Exhibit, 25 May 2017. Photograph by Yvonne Burt

Auerbach often said his goal with each work was to create a living presence, a thing with life independent of its creator. After nearly a decade sitting beside the Head of Gerda Boehm, she became for me that living presence. I knew the role Gerda Boehm had played in Auerbach’s life after he came to London, learned she’d been one of his regular sitters in the seventies, discovered my Gerda Boehm had been one of his paintings that represented Britain in the 1986 Venice Biennale at which he won the Lion d’Or. Slowly I began to think I understood the Head of Gerda Boehm, and to test that perception

I wrote ‘Modern Painters’.

Detail of Head of Gerda Boehm. Frank Auerbach. Photograph: Paul Hodgson. Copyright © Estate of Frank Auerbach. Courtesy of Frankie Rossi Gallery

Auerbach was more than the subject of Modern Painters, he was an exemplar when I began trying seriously to write poetry. With his oeuvre in mind, I chose the first half of the poem’s second stanza’s opening line – We look like this – as the title of my first poetry collection, and with Auerbach’s permission used the Gerda Boehm image on its dust jacket.

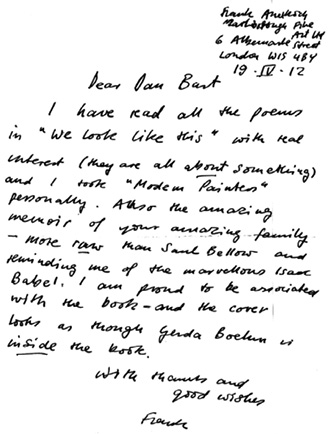

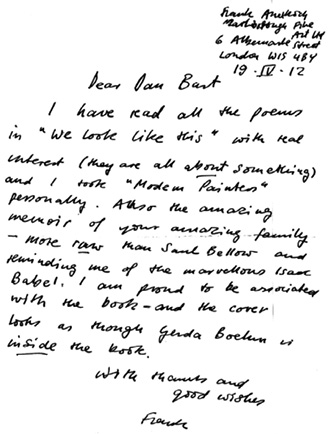

Courtesy demanded I send him a copy of the book on publication. Therefore despite terror at being revealed as an imposter, I sent him a copy of We Look Like This, the Head of Gerda Boehm covering the dust jacket, Modern Painters inside testifying to my small understanding of his art. A few days later I received the following letter:

Copyright © Estate of Frank Auerbach

In the last dozen years of Frank Auerbach’s life, the ones after I received his note and I came to know him better, he continued to paint and live as he had all his creative life. He developed a late style – less impasted, brighter, easier to read, vibrant – that produced nonpareil work. Skulls began appearing in cityscapes and studio pictures, as age inevitably ambushed him. The plaudits he never chased rained on him. His major retrospective at Tate Britain was rapturously reviewed.

Covid lockdown deprived him of his sitters, so he drew and painted self-portraits and views of his studio which drew clamorous praise. A two-room exhibition last year of his charcoal heads from 1954–6 notched the Courtauld’s highest visitor numbers ever for a three-month show.

But painting inexorably became harder as his heart weakened. Two months ago he entered hospital to explore what help surgery might be. “Little” said the doctors. Soon after leaving hospital time pried the brush from his hand. Two weeks later he was dead.

All my paragons have had clay feet, except Frank Auerbach.

He died last week at the age of ninety-three, universally eulogized as ‘the greatest living artist’1 of his time. ‘With the death of [Francis] Bacon in 1992 and [Lucian] Freud in 2011, he became a leading contender for the unofficial title “greatest living British artist.”’2 “He will be remembered as an […] artist whose contribution to portraiture and landscape painting has had no equal during his long lifetime.”3 From this judgment none dissent.

He was not a world-famous artist in 1994 when I was walking down Albemarle Street towards Piccadilly late on an Indian summer's afternoon and a painting of a head in a gallery window arrested me. Frank Auerbach, the name stencilled on Marlborough Gallery’s window above the painting, was new to me, a recent émigré to London from D.C. and newcomer to the British art world. With a half hour before the gallery closed, I entered.

On the light grey walls inside hung some twenty paintings, mostly portrait size heads (24” x 24”), a few cityscapes twice that size, and several drawings. All the paintings were heavily impasted, the paint almost sculptural, with thick slashes of black and primary colours scarring the canvases. They were indecipherable until I found the right distance from which to view them; even then heads, figures, streets and buildings were barely discernible. Not all had been sold.

But they rooted in my memory. By 1994 Auerbach had been painting and drawing for some forty-five years. A succès d’estime in Britain almost from the first, the London art world – artists, critics, scholars, major collectors – over time increasingly lauded him. Among fellow figurative artists, dubbed the School of London – Michael Andrews, Bacon, Freud, R.B. Kitaj, Leon Kossoff – he was legendary: for his sad childhood, his work habits, above all his artistic practice. He was the only contemporary Lucian Freud collected in depth.

Auerbach’s Jewish parents dispatched him, alone, to Britain from Berlin as an eight-year-old refugee in 1938. There for ten years he boarded at Bunce Court, a progressive Quaker school in Kent. The Germans had murdered his parents somewhere in the camps by the end of 1942, leaving Gerda Boehm, a much older cousin in North London, his only living relative.

By the time he graduated from the Royal College of Art in 1955 he had developed the fundamentals of his impasted, compulsively reworked, almost abstract style of figuration. He had a small circle of sitters, and a few cityscapes, that he drew and painted repeatedly his whole career. Every morning he scraped off or erased what he had painted or drawn the night before, time and again, till the image embodied what he called the ‘raw truth’. With paintings this reworking might build up a thick base you could carve with a palette knife; with drawings it often wore holes in the paper he then patched. Both methods created palimpsests one sensed beneath the final image. Such was his style from his debut show at London’s Beaux Arts Gallery in 1956 until his death sixty-eight years later.

More than his craft was sui generis. He painted 364 days a year, taking off only Christmas Day. For thirty-three years he lived seven days a week in his one room studio in Camden’s Mornington Crescent area; from 1987 until his death he lived there three. Until his last decade he almost invariably refused interviews. Openings, his own included, he gave a miss, likewise dinner parties. He refused a knighthood; after his fame escaped gravity he declined to become a Companion of Honour, explaining that it would have been a distraction, bringing with it unwanted personal attention.

I knew none of this, nor had I met him, when I bought his Head of Gerda Boehm (1978–9) at auction in 1996. Sotheby’s put it in a ‘Day Sale’ at which they offer less expensive art than in their evening sales. His paintings which had haunted me since I first saw them at Marlborough came clearly to mind when I saw the Gerda Boehm image in Sotheby’s catalogue. But the Gerda Boehm was even more striking than the paintings I remembered, its guide price a third less. I readied my paddle.

Ever since, the Head of Gerda Boehm has hung four feet to the right of my desk. For near three decades I’ve looked at it every day when I sit down to work. When my eyes lift from my laptop I often swivel to Gerda Boehm; never does she age or stale, the hallmark of great art.

During my first decade in London, lawyering and a long-standing interest in art conjoined to involve me deeply in the British art world. I met Kitaj, Paula Rego and Anish Kapoor amongst other noted British artists. But it was to Auerbach I returned most often.

I grew familiar with his oeuvre from seeing it in exhibitions and catalogues. The essays in them, as well as reviews, monographs and occasional interviews taught me about his style, habits and aesthetic aims. From his sitters, dealers, curators, scholars I learned of the physical labour that making his art required, his erudition and his love of poetry. And from all these sources, especially interviews in his last decade, shone his extraordinary articulateness, thoughtfulness and profound understanding of his craft.

Frank Auerbach was no curmudgeonly recluse, no anchorite. Obsession had no purchase on his character. Warm, friendly, a wonderful dinner companion, dedicated. He chose not to travel or socialize because, as he said in one late interview, when he got up in the morning he could think of nothing better to do than paint, and so he did.

Fame did not change him. He had no ‘side’, never denigrating other artists, sympathetic to poor sinners who must paint for their dinners, to those whose careers never caught fire. He visited museums and galleries at times when there were few other visitors or none, the better to study the art displayed. An artist I knew ran into him more than once at these shows, as did I at the Royal Academy’s Hockney Exhibition in May 2017.

Frank and Julia Auerbach at David Hockney Exhibit, 25 May 2017. Photograph by Yvonne Burt

Auerbach often said his goal with each work was to create a living presence, a thing with life independent of its creator. After nearly a decade sitting beside the Head of Gerda Boehm, she became for me that living presence. I knew the role Gerda Boehm had played in Auerbach’s life after he came to London, learned she’d been one of his regular sitters in the seventies, discovered my Gerda Boehm had been one of his paintings that represented Britain in the 1986 Venice Biennale at which he won the Lion d’Or. Slowly I began to think I understood the Head of Gerda Boehm, and to test that perception

I wrote ‘Modern Painters’.

He trowels white, ochre, builds a base,

carves, smears, slashes, waits…

with black strokes carves a flayed face

on the impasted canvas. Next day erase,

daub on paint again, again efface,

repeat till a palimpsestic skin’s in place

and the sitter’s flesh replaced

with grey slabs like rotting salmon filets.

We look like this after things fall apart,

the painting merely an autopsy report

on the corpse war dumped on the coroner’s cart.

He lifts a palette-knife to start:

invade, split rib cage, spread thought apart,

slit pericardium, sound cankered heart,

anatomize the entrail’s parts,

that heap of faiths and old philosophies

encasing the mean midden of descent

and express the ravaged guts of a continent –

gas chambers, burn pits, barbed wire ligaments –

slaughter so savage horror itself is spent.

Freighted with these painted lineaments

the curtain falls on the Enlightenment

like Luftmenschen4 ash on the Red regiments

storming west through Poland from Stalingrad.

Detail of Head of Gerda Boehm. Frank Auerbach. Photograph: Paul Hodgson. Copyright © Estate of Frank Auerbach. Courtesy of Frankie Rossi Gallery

Auerbach was more than the subject of Modern Painters, he was an exemplar when I began trying seriously to write poetry. With his oeuvre in mind, I chose the first half of the poem’s second stanza’s opening line – We look like this – as the title of my first poetry collection, and with Auerbach’s permission used the Gerda Boehm image on its dust jacket.

Courtesy demanded I send him a copy of the book on publication. Therefore despite terror at being revealed as an imposter, I sent him a copy of We Look Like This, the Head of Gerda Boehm covering the dust jacket, Modern Painters inside testifying to my small understanding of his art. A few days later I received the following letter:

Copyright © Estate of Frank Auerbach

In the last dozen years of Frank Auerbach’s life, the ones after I received his note and I came to know him better, he continued to paint and live as he had all his creative life. He developed a late style – less impasted, brighter, easier to read, vibrant – that produced nonpareil work. Skulls began appearing in cityscapes and studio pictures, as age inevitably ambushed him. The plaudits he never chased rained on him. His major retrospective at Tate Britain was rapturously reviewed.

Covid lockdown deprived him of his sitters, so he drew and painted self-portraits and views of his studio which drew clamorous praise. A two-room exhibition last year of his charcoal heads from 1954–6 notched the Courtauld’s highest visitor numbers ever for a three-month show.

But painting inexorably became harder as his heart weakened. Two months ago he entered hospital to explore what help surgery might be. “Little” said the doctors. Soon after leaving hospital time pried the brush from his hand. Two weeks later he was dead.

- Waldemar Januszczak, The Sunday Times, 17 November 2024.

- New York Times, 1 November 2024

- The Art Newspaper, December 2024.

- Death camp inmates referred to the ash blowing from the crematoria smokestacks as Luftmensch(en) (literally air persons). It is Yiddish for an unworldly, impractical man.

This report is taken from PN Review 281, Volume 51 Number 3, January - February 2025.