This article is taken from PN Review 284, Volume 51 Number 6, July - August 2025.

The Library as Macrocosm and Microcosm

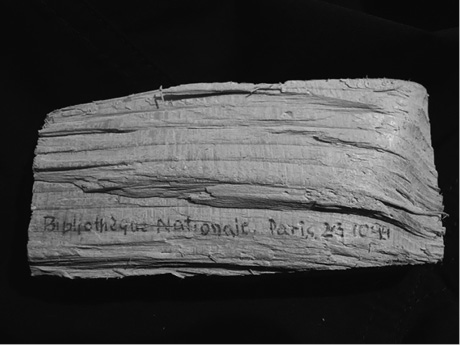

The closing lecture at the Bibliothèque de France in Paris to celebrate its thirtieth anniversary

On 23 October 1994, I decided to visit the much-vaunted site in Bercy where the new national library of France was going to be built. Much earlier, when I was in my twenties, I had gone to read in the old library, the one on the Rue Richelieu, to research for the Dictionary of Imaginary Places that I was writing with my friend, Gianni Guadalupi. And because that was the first national library of France I knew, for me, that noble building and its stately Salle Labrouste were (perhaps in my mind still are) an indelible monument in my private French geography. First loves are often the ones that remain steadfast and are blind to factual reason.

National libraries, whether almost mythical ones such as that of Alexandria, or almost too down-to-earth ones such as the Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine, are above all symbolic buildings. They incarnate the identity of their readers, be they ambitious kings or resilient victims, reflecting back to them what these men and women, as readers, have understood to be their cultural and political memory, their language and their literature, the evidence of their existence and the inspiration of their mythologies. Ordinary libraries, whether private or public, are worlds defined by their chosen contents and their selective use. A national library, however, is the vaster universe that echoes and preserves them. A private library is an autobiography told in the voice of its reader, but a national library is the collective answer to the curse of Babel, alchemically transforming the linguistic chaos ...

The page you have requested is restricted to subscribers only. Please enter your username and password and click on 'Continue':

If you have forgotten your username and password, please enter the email address you used when you joined. Your login details will then be emailed to the address specified.

If you are not a subscriber and would like to enjoy the 293 issues containing over 11,700 poems, articles, reports, interviews and reviews,

why not subscribe to the website today?