Your magazine is excellent.

Octavio Paz

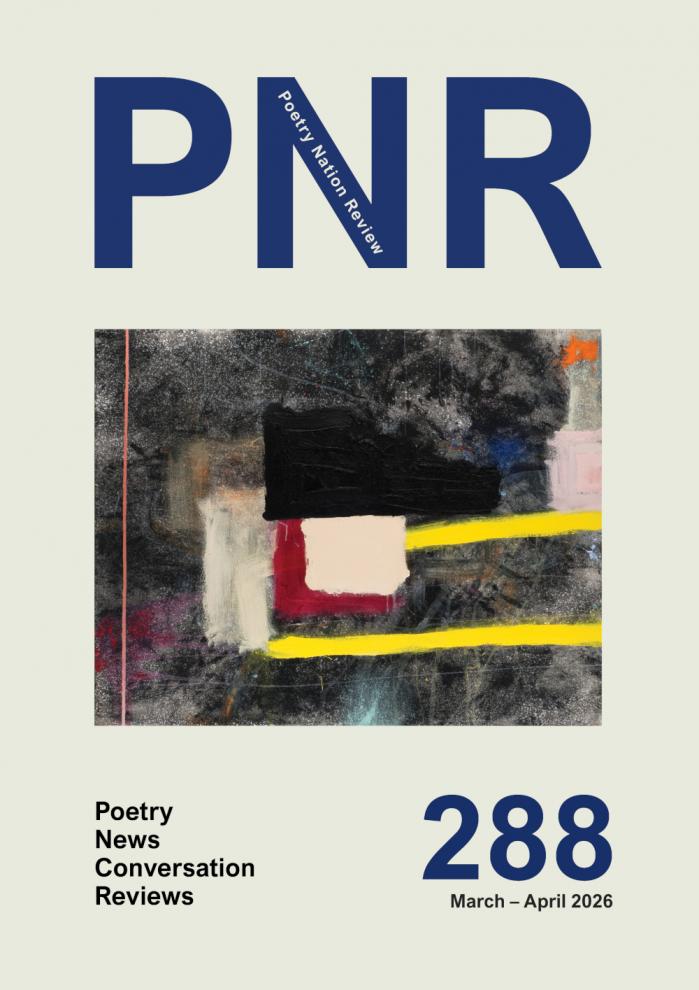

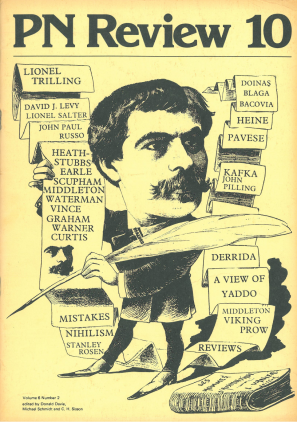

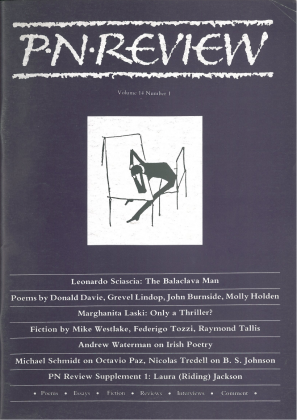

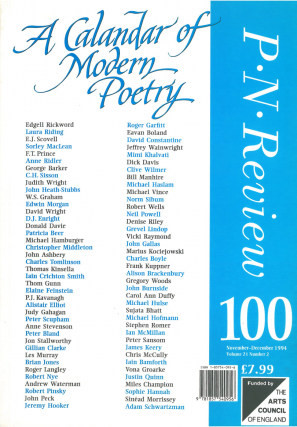

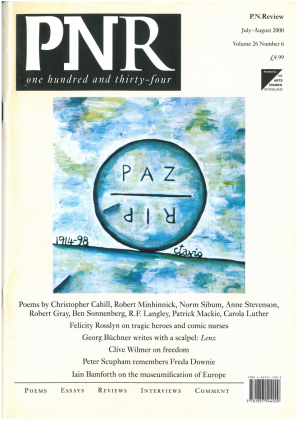

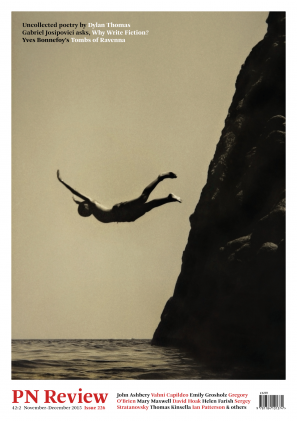

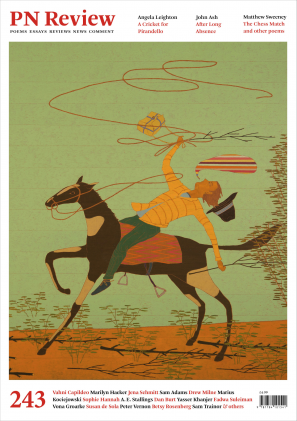

Since we started as Poetry Nation, a twice-yearly hardback, in 1973, we've been publishing new poetry, rediscoveries, commentary, literary essays, interviews and reviews from around the globe. In 2023 PN Review celebrated its jubilee.

Our vast archive now includes over 280 issues, with contributions from some of the most exciting and radical writers of our times. Key contributors include Octavio Paz, Laura Riding, Christopher Middleton, John Ashbery, Les Murray, Patricia Beer, W.S. Graham, Eavan Boland, Jorie Graham, Donald Davie, C.H. Sisson, Sinead Morrissey, Sasha Dugdale, Anthony Vahni Capildeo, and many others.

Our vast archive now includes over 280 issues, with contributions from some of the most exciting and radical writers of our times. Key contributors include Octavio Paz, Laura Riding, Christopher Middleton, John Ashbery, Les Murray, Patricia Beer, W.S. Graham, Eavan Boland, Jorie Graham, Donald Davie, C.H. Sisson, Sinead Morrissey, Sasha Dugdale, Anthony Vahni Capildeo, and many others.

Subscribe to PN Review

SUBSCRIBEFrom the Archive

in Conversation with Robert MinhinnickRobert Minhinnick was born, in 1952, and brought up in the village of Pen-y-fai, near Bridgend, south Wales. He was first published in the 'New Poets' special number of Poetry Wales in 1972 and has since established himself at the forefront of the younger generation of Anglo-Welsh writers. The most recent of his six books of poetry, Hey Fatman, was published by Seren in 1994. He has also produced two volumes of essays, Watching the Fire Eater, Arts Council of Wales Book of the Year in 1993, and Badlands (1996):

SAM ADAMS: Although you are clearly Welsh by birth, upbringing and allegiance, in a country where the list of writers is packed with Davieses, Joneses and Thomases, your name is unusual. Is Minhinnick Cornish? More importantly, are you interested in origins?

ROBERT MINHINNICK: ... READ MORE

Readers' Choices

Rebecca Watts

(PN Review 239)

Stav Poleg

(PN Review 279)

Rory Waterman

(PN Review 286)

Stav Poleg

(PN Review 276)

Eavan Boland

(PN Review 121)

(PN Review 239)

Stav Poleg

(PN Review 279)

Rory Waterman

(PN Review 286)

Stav Poleg

(PN Review 276)

Eavan Boland

(PN Review 121)

Subscribe to our Substack to receive curated items from our archive.

SIGN UP