This item is taken from PN Review 282, Volume 51 Number 4, March - April 2025.

News & Notes

Goodbye Michael Longley • John McAuliffe writes: The poet Michael Longley has died at the age of eighty-five. Born in Belfast, he was educated there at Inst, where Derek Mahon was a contemporary, and the two went on to study at Trinity College, Dublin. Fellow students included Eavan Boland and Longley’s future wife Edna Broderick. His classics degree, and his careful attention to line and syntax, would give body and bottom to his poems’ emotional range, from wit and whimsy to passionate anger, in fine, acclaimed books, including The Echo Gate, Gorse Fires, The Weather in Japan and, last year, a new Selected Poems, Ash Keys.

Belfast and the Troubles are the subject of many of his best-known poems, but he also spent five decades visiting a coastal corner of County Mayo. Its locals, wildflowers and fauna are reliable denizens of his collections whose covers were often adorned by his daughter Sarah’s drawings. He also edited admiring selections of Robert Graves, John Hewitt (co-edited with Frank Ormsby) and Louis MacNeice, writers whose poetics he opposed to what he saw as a Modernist wrong turn.

Longley worked as Director of Combined Arts at the Northern Irish Arts Council from 1970 until early retirement 1991, and is remembered, along with his colleague there, the poet Ciaran Carson, for his encouragement of traditional arts and community arts, as well as new publishers and younger poets, including Paul Muldoon, Medbh McGuckian, Gail McConnell and Leontia Flynn.

A fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and a member of Aosdána, he was awarded the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry in 2001, and from 2007 to 2010 held the post of Ireland Professor of Poetry. He was made a CBE in 2010 and, in 2022, was awarded the Feltrinelli International Poetry Prize. These honours, and the Whitbread and TS Eliot Prizes, recognised his stature as a significant poet in a remarkable generation.

A scion of the ‘downmarket universities’ • Jeffrey Wainwright writes: Brian Maidment died on 27 January 2025. His anthology The Poorhouse Fugitives (1992), published by Carcanet, brought the work of self-taught poets of Victorian Britain to serious attention through its first-hand research in the journals of the period and his own judicious commentaries on the work. This interest was in part a development of his earliest research interest, revisited towards the end of his career, in John Ruskin.

Brian’s fascination with the popular prints of the nineteenth century, both in literature and visual art, dominated his subsequent work. All of his research was based in thoroughgoing work on primary sources and brought him great acclaim among fellow scholars of the period. His books for Manchester University Press include Dusty Bob: A Cultural History of Dustmen 1780–1870, which took its inspiration from the presence of ‘dust’ in Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend, and Comedy, Caricature and the social order 1820–1850.

It may or may not be because of his work in this unfancied area of cultural history that his academic posts were mostly at what he jokingly referred to as ‘downmarket’ universities, beginning at Aberystwyth and then at Manchester Metropolitan, Edge Hill, Huddersfield, Salford and Liverpool John Moores, where he was research professor in the History of Print. In all of these, however, he was a valuable, well-liked colleague with a deep attachment to undergraduate teaching. Latterly he did work in the more prestigious environs of Yale’s Beineke Library, where he was regularly asked to conduct graduate seminars. Brian was an original scholar and a great colleague and friend.

Patrolling Hadrian’s Wall • Bloodaxe Books announced the death of their Dutch poet and archaeologist Esther Jansma (1958–2025). In 2004 she took part in Writing on the Wall, a five-year international programme involving writers from the north of England, Scotland as well as countries which originally garrisoned Hadrian’s Wall. Francis R. Jones’s translation, What It Is: Selected Poems (2008), was the first in English of her work, drawing on all the collections she had published in the Netherlands at that time, and including poems inspired by parts of Hadrian’s Wall where Friesian and Schelt auxiliaries were stationed.

As an archaeologist she refined a technique for establishing the age of wooden artefacts from growth rings in the wood, which could be applied to timber from the Netherlands. Lending a voice to the past, making time visible in all its aspects, is also what she did in her poetry. In her early work, the voices of the past are heard from bewildering years: as a child, the death of a father, then as a mother, the loss of a child. Her later poetry is less personal but more compelling as her poetic universe expanded.

She told Bloodaxe editor Neil Astley that she thought Jones’s translations were extraordinary in how he had been able to recreate the sounds and rhythms of her Dutch poems in English as well as evoking her tone and style without sacrificing any of the meaning.

She died from cancer at a hospice in Utrecht aged sixty-six.

A new era at Literary Imagination • PN Review contributor Paul Franz has been named editor of Literary Imagination, the flagship journal of the Washington, DC, based Association of Literary Scholars, Critics, and Writers (alscw.org). The March 2025 issue will be the first of Dr Franz’s tenure and the first to be published by the Johns Hopkins University Press, thereby inaugurating a new era after a long and fruitful relationship with Oxford University Press. Featuring Herbert Marks on the Bible; Blake Smith on Alan Ansen; Yulia Ryzhik on Spenser’s Gnat; reviews of works by Han Kang and Maggie Millner by Tae Ho Kim and Karl Kirchwey, respectively; and a symposium on the late poet David Ferry by divers hands; not to mention original poems and translations of Enrico Testa and Catullus, the issue exemplifies the heterogeneity as well as the chronological and cultural sweep that have distinguished the journal from its founding in 1999. First-time subscriptions, which include membership in the ALSCW, cost US$75 and may be purchased here: https://alscw.press.jhu.edu/membership/join.

Welcome to The Little Review • Tristram Fane-Saunders draws our attention to the launch of an unusual magazine. The Little Review (not to be confused with the original The Little Review) is a pocket-hanky sized magazine with a handsome website (https://www.thelittlereview.co.uk/). It seems to be hungry for Poems and Features and Gossip and Reviews and Essays and Insolence and Triviality and Poems and… The carousel, like the whirligig of time, brings round its revenges. What makes the magazine unusual, apart from its size, is its approach to submissions. ‘I’ve heard a few very experienced poetry journal editors complaining about two recurring problems: A) drowning in far too many submissions of poems, and B) struggling to get enough good critical prose’, says Tristram Fane-Saunders. ‘The Little Review might have a novel solution to both problems: contributors can send in as many poems as they like, so long as they submit at least one book review per poem.’ The editor imagines that there are poets out there who still read poetry by other people and are capable of reviewing it. We are promised a free copy of the first issue: maybe our readers should look at the website and subscribe… There is also a free weekly email newsletter available via Substack.

Technology’s absolution • A ship’s navigator told me last month that the most recent recruits who come to work alongside him generally don’t know how to read old-fashioned maps and charts and, much less, the sky. Technology has absolved them of the need for such knowledge, they seem to believe. Clearly they have not been prepared for the failure of technology or the withdrawal of technological resources – something which is not unthinkable given the ‘new world order’ and its patterns of ownership and control.

This came to mind as I read a compelling meditation on the future of book publishing and of the book itself, issued by Andrew Rhomberg on his LinkedIn page (https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/future-book-publishing-2025-beyond-andrew-rhomberg-bxdpe/). It concludes with what he calls ‘The Reading Gap’:

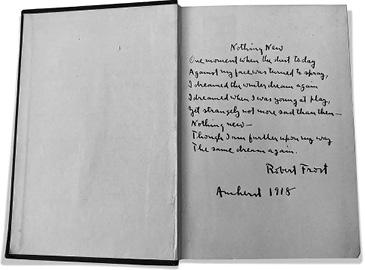

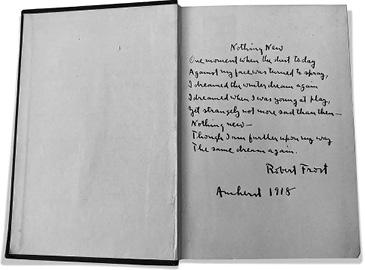

The New Yorker as part of its hundredth birthday celebrations published a previously uncollected poem by Robert Frost. There was much commentary about the poem, though this did not concentrate on the prosody of the closing lines, the sudden diminution from eight to three syllables, then nine and finally five, as though the poem was dissolving into the kind of free verse Edward Thomas, Frost’s friend in England, was practising. Thomas died in 1917.

Belfast and the Troubles are the subject of many of his best-known poems, but he also spent five decades visiting a coastal corner of County Mayo. Its locals, wildflowers and fauna are reliable denizens of his collections whose covers were often adorned by his daughter Sarah’s drawings. He also edited admiring selections of Robert Graves, John Hewitt (co-edited with Frank Ormsby) and Louis MacNeice, writers whose poetics he opposed to what he saw as a Modernist wrong turn.

Longley worked as Director of Combined Arts at the Northern Irish Arts Council from 1970 until early retirement 1991, and is remembered, along with his colleague there, the poet Ciaran Carson, for his encouragement of traditional arts and community arts, as well as new publishers and younger poets, including Paul Muldoon, Medbh McGuckian, Gail McConnell and Leontia Flynn.

A fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and a member of Aosdána, he was awarded the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry in 2001, and from 2007 to 2010 held the post of Ireland Professor of Poetry. He was made a CBE in 2010 and, in 2022, was awarded the Feltrinelli International Poetry Prize. These honours, and the Whitbread and TS Eliot Prizes, recognised his stature as a significant poet in a remarkable generation.

A scion of the ‘downmarket universities’ • Jeffrey Wainwright writes: Brian Maidment died on 27 January 2025. His anthology The Poorhouse Fugitives (1992), published by Carcanet, brought the work of self-taught poets of Victorian Britain to serious attention through its first-hand research in the journals of the period and his own judicious commentaries on the work. This interest was in part a development of his earliest research interest, revisited towards the end of his career, in John Ruskin.

Brian’s fascination with the popular prints of the nineteenth century, both in literature and visual art, dominated his subsequent work. All of his research was based in thoroughgoing work on primary sources and brought him great acclaim among fellow scholars of the period. His books for Manchester University Press include Dusty Bob: A Cultural History of Dustmen 1780–1870, which took its inspiration from the presence of ‘dust’ in Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend, and Comedy, Caricature and the social order 1820–1850.

It may or may not be because of his work in this unfancied area of cultural history that his academic posts were mostly at what he jokingly referred to as ‘downmarket’ universities, beginning at Aberystwyth and then at Manchester Metropolitan, Edge Hill, Huddersfield, Salford and Liverpool John Moores, where he was research professor in the History of Print. In all of these, however, he was a valuable, well-liked colleague with a deep attachment to undergraduate teaching. Latterly he did work in the more prestigious environs of Yale’s Beineke Library, where he was regularly asked to conduct graduate seminars. Brian was an original scholar and a great colleague and friend.

Patrolling Hadrian’s Wall • Bloodaxe Books announced the death of their Dutch poet and archaeologist Esther Jansma (1958–2025). In 2004 she took part in Writing on the Wall, a five-year international programme involving writers from the north of England, Scotland as well as countries which originally garrisoned Hadrian’s Wall. Francis R. Jones’s translation, What It Is: Selected Poems (2008), was the first in English of her work, drawing on all the collections she had published in the Netherlands at that time, and including poems inspired by parts of Hadrian’s Wall where Friesian and Schelt auxiliaries were stationed.

As an archaeologist she refined a technique for establishing the age of wooden artefacts from growth rings in the wood, which could be applied to timber from the Netherlands. Lending a voice to the past, making time visible in all its aspects, is also what she did in her poetry. In her early work, the voices of the past are heard from bewildering years: as a child, the death of a father, then as a mother, the loss of a child. Her later poetry is less personal but more compelling as her poetic universe expanded.

She told Bloodaxe editor Neil Astley that she thought Jones’s translations were extraordinary in how he had been able to recreate the sounds and rhythms of her Dutch poems in English as well as evoking her tone and style without sacrificing any of the meaning.

She died from cancer at a hospice in Utrecht aged sixty-six.

A new era at Literary Imagination • PN Review contributor Paul Franz has been named editor of Literary Imagination, the flagship journal of the Washington, DC, based Association of Literary Scholars, Critics, and Writers (alscw.org). The March 2025 issue will be the first of Dr Franz’s tenure and the first to be published by the Johns Hopkins University Press, thereby inaugurating a new era after a long and fruitful relationship with Oxford University Press. Featuring Herbert Marks on the Bible; Blake Smith on Alan Ansen; Yulia Ryzhik on Spenser’s Gnat; reviews of works by Han Kang and Maggie Millner by Tae Ho Kim and Karl Kirchwey, respectively; and a symposium on the late poet David Ferry by divers hands; not to mention original poems and translations of Enrico Testa and Catullus, the issue exemplifies the heterogeneity as well as the chronological and cultural sweep that have distinguished the journal from its founding in 1999. First-time subscriptions, which include membership in the ALSCW, cost US$75 and may be purchased here: https://alscw.press.jhu.edu/membership/join.

Welcome to The Little Review • Tristram Fane-Saunders draws our attention to the launch of an unusual magazine. The Little Review (not to be confused with the original The Little Review) is a pocket-hanky sized magazine with a handsome website (https://www.thelittlereview.co.uk/). It seems to be hungry for Poems and Features and Gossip and Reviews and Essays and Insolence and Triviality and Poems and… The carousel, like the whirligig of time, brings round its revenges. What makes the magazine unusual, apart from its size, is its approach to submissions. ‘I’ve heard a few very experienced poetry journal editors complaining about two recurring problems: A) drowning in far too many submissions of poems, and B) struggling to get enough good critical prose’, says Tristram Fane-Saunders. ‘The Little Review might have a novel solution to both problems: contributors can send in as many poems as they like, so long as they submit at least one book review per poem.’ The editor imagines that there are poets out there who still read poetry by other people and are capable of reviewing it. We are promised a free copy of the first issue: maybe our readers should look at the website and subscribe… There is also a free weekly email newsletter available via Substack.

Technology’s absolution • A ship’s navigator told me last month that the most recent recruits who come to work alongside him generally don’t know how to read old-fashioned maps and charts and, much less, the sky. Technology has absolved them of the need for such knowledge, they seem to believe. Clearly they have not been prepared for the failure of technology or the withdrawal of technological resources – something which is not unthinkable given the ‘new world order’ and its patterns of ownership and control.

This came to mind as I read a compelling meditation on the future of book publishing and of the book itself, issued by Andrew Rhomberg on his LinkedIn page (https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/future-book-publishing-2025-beyond-andrew-rhomberg-bxdpe/). It concludes with what he calls ‘The Reading Gap’:

A worrying trend has been the increasing decline in literacy and reading among young readers.Happy Birthday to the New Yorker!

The National Literacy Trust in the UK has been conducting annual surveys and these show that children are spending less and less time reading in their free time. Interest in books has been declining steadily.

The reasons are unclear, but social media, cost pressures at home, and other factors seem to be at play. The predicted outcome is clear though: there will be fewer readers who are interested in purchasing books in the future and this should have the industry as a whole worried!

The trend is not specific to the UK. In 2018, the Börsenverein – the German Publisher and bookseller association – note in its landmark study ‘Buchkäufer – quo vadis?’ that the number of German book buyers was declining. This trend has continued and is also witnessed in many other parts of the world. An article in the Atlantic recently highlighted that students even at elite colleges were struggling to read books in full, a problem that is a direct result of less reading in school.

This is a frightening outlook for the book publishing industry as a whole, because it means audience is shrinking unless the reading gap in school can be closed.

There are many theories as to why young readers are giving up on books – distraction by smartphones and social media, changing societal habits such as parents no longer reading with their children, competition from computer games, Netflix and other forms of entertainment. However, there is precious little research as to what the genuine reason is and how young readers might be lured back.

It is one of the main ambitions at Jellybooks (Andrew Rhomberg’s research company) to conduct more quantitative research in this area in 2025 by applying our reader analytics and cloud-based tools in partnership with schools, charities, publishers and the Arts Council England, to find out how the reading gap might be bridged for the benefit of the industry as a whole.

The New Yorker as part of its hundredth birthday celebrations published a previously uncollected poem by Robert Frost. There was much commentary about the poem, though this did not concentrate on the prosody of the closing lines, the sudden diminution from eight to three syllables, then nine and finally five, as though the poem was dissolving into the kind of free verse Edward Thomas, Frost’s friend in England, was practising. Thomas died in 1917.

This item is taken from PN Review 282, Volume 51 Number 4, March - April 2025.