This article is taken from PN Review 281, Volume 51 Number 3, January - February 2025.

Borges, Recursion and the MultiverseSome Reflections

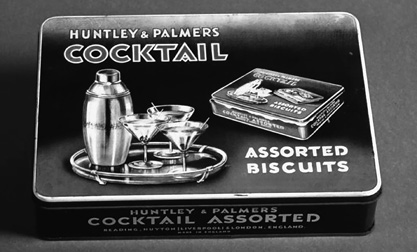

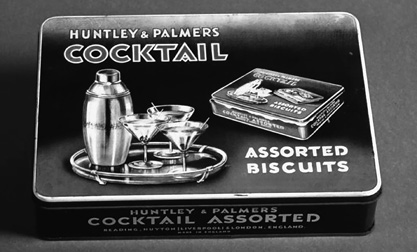

In his essay ‘When Fiction Lives in Fiction’ (1939), Borges states that he can trace his first notion of the problem of infinity to a large biscuit tin that lent ‘mystery and vertigo’ to his childhood. ‘On the side of this unusual object,’ he writes, ‘there was a Japanese scene; I cannot remember the children or warriors depicted there, but I do remember that in a corner of that image the same biscuit tin reappeared with the same picture, and within it the same picture again, and so on (at least, potentially) into infinity...’1

This childhood experience of Borges’s, in turn, evokes the vertigo the reader might feel before the various mysteries and labyrinths, the doublings and redoublings, and the recursive modes of narration that populate so many of the author’s stories. And it is this notion of recursion (or recurrent self-referentiality) that I wish to address and explore today.

Of course, I don’t know what biscuit tin Borges had in mind, but I definitely remember this one, from my own childhood, which, like his, contains on the lid an image of itself, and within that image another, and so on ad infinitum. Like the young Borges, I remember being enthralled by the image.

A dozen or so years ago I was invited by the Argentine newspaper Clarín to write a piece commemorating the twenty-fifth anniversary of Borges’s death. At around the same time, as chance would have it, I wrote a piece for the British newspaper the Independent for their series ‘Book of a Lifetime’, in which writers were invited to contribute short summaries of a favourite book. I chose Borges’s Fictions, and claimed that ‘other books have had a powerful impact on me, but none marked a turning-point in my understanding of the world and the written word in quite the same way’. In both articles I began by describing the circumstances in which I was living when I first came across the work of the Argentine author, more or less as I record them here.

I discovered Borges’s short stories at the age of eighteen, when I was living in an abandoned shepherd’s hut at the foot of a mountain named Keratókambos, on the island of Crete. I found the place while exploring a deserted stretch of the south coast of the island, and moved in for the summer. I had a few books with me;

I had just devoured The Brothers Karamazov and The Magic Mountain in rapid succession, and the brevity and intensity of Borges’s writing came as a revelation. Borges himself had something to say about big novels, as he articulated in the Prologue to Ficciones (1944): ‘The composition of vast books is a laborious and impoverishing extravagance. To go on for five hundred pages developing an idea whose perfect oral exposition is possible in a few minutes! A better course of procedure is to pretend that these books exist and then to offer a résumé, a commentary.’2 The idea that instead of writing voluminous books we can simply pretend that they exist had a profound appeal to the budding writer in me, horrified at the interminable exposition of those mighty tomes by Dostoyevsky and Mann. Borges’s ludic style and brevity were much more attractive, and there was something enormously liberating, a kind of weightlessness, to the idea that by minimising the word count we might invoke extraordinary worlds without having to set them down with wearisome description, endless exposition and fatuous dialogue. If only things were so simple. The brevity of a literary work does not diminish its complexity, and the worlds one encounters in Borges’s compact stories contain multitudes.

Fiction within Fiction

But more than anything else, all those years ago, I was seduced by the idea that every instant contains the potential for an infinity of outcomes – a recurring motif in Borges’s work – or that our universe is only one in a multiplicity of possible universes; or, less appealingly, that rather than being the proprietors of our own consciousness, we are being dreamed by some other entity. These are not comfortable ideas to live with, pushing, as they do, at the edges of comprehension. Always dissatisfied with received wisdoms, these ideas took a hold on me early in life, and I have never abandoned them, nor felt inclined to do so.

Borges concludes his essay on ‘When Fiction Lives in Fiction’ with a summary of Flann O’Brien’s novel At Swim-Two-Birds (which, it might be noted, he reviewed in the magazine El Hogar only six months after it first appeared in English), in which a young student from Dublin writes a novel about a publican from that city, who in turn writes a novel about his customers, one of whom is the student author; and he quotes Schopenhauer’s comment, ‘that dreaming and wakefulness are the pages of a single book, and that to read them in order is to live, and to leaf through them at random, to dream. Paintings within paintings and books that branch off into other books help us sense this oneness.’ In other words, the perspective that one story was a vehicle for other stories, and that the process could become one of unlimited recursion, was established quite early in the writer’s career, and over time it became a hallmark of his literary oeuvre.

A fundamental principle within the study of linguistics is that, in spoken language, an idea can be contained within an idea, a phrase within a phrase. This forms the basis of recursion in grammar. Noam Chomsky has claimed that it is the essential tool that underlies all of the creativity of human language. In theory, according to Chomsky, an infinitely long, recursive sentence is possible, since there is no limit to the mind’s capacity to embed one thought within another. Our language is recursive because our minds are recursive.

A parody of the opening sentence of a now-forgotten novel, Paul Clifford, by the nineteenth-century English novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton, might serve as an initial illustration of recursion – ‘It was a dark and stormy night, and we said to the captain: “Tell us a story!” And this is the story the captain told: “It was a dark and stormy night, and we said to the captain, ‘Tell us a story!’ And this is the story the captain told: ‘It was a dark and stormy night ”’’...

Another exercise in recursion would be the English nursery rhyme about an old lady who swallows a fly, which, as the song’s chorus repeats, ‘wriggled and jiggled and tickled inside her’. The unfortunate woman decides to swallow a spider in order to catch the fly, and then successively, a bird to catch the spider, a cat to catch the bird, a dog to catch the cat, and so on in a theoretically infinite number of permutations. This gruesome little song neatly exemplifies the nature of recursion and, as I discovered, is even used as an illustration in a computer science programming manual on that topic. An article on recursive thinking in American Scientist points out that the realisation that one has thoughts about one’s own thoughts itself constitutes a theory of mind.3 René Descartes is renowned for the phrase cogito, ergo sum (although he actually wrote ‘je pense, donc je suis’: I think, therefore I am). Descartes presented this utterance as proof of his own existence, and although he sometimes doubted it, the doubt was itself a mode of thinking, so his real existence was not in doubt. The phrase is fundamentally recursive, since it involves not only thinking, but thinking about thinking.

Remembering a particular episode from one’s own life suggests a recursive projection of oneself out of the present moment. In the novel À la recherche du temps perdu, Marcel Proust returns to various projections of episodic memory, including the famous moment when the taste of a petite madeleine evokes the memory of a past event in the narrator’s mind. In terms of the present text, we might consider as recursive the references I made a few moments ago, when I said that I started an article in Clarín twelve years ago with (almost) the same words that I used today, or when I recited the words: ‘All those years ago, I was seduced by the idea that every instant contains the potential for an infinity of outcomes.’

The notion of recursion is also the driving force behind fractals, complex patterns that are self-replicating across different scales. Fractals are created by repeating a simple process over and over in an ongoing feedback loop. It has been claimed that the coast of Brittany has the characteristics of a fractal, for example, and we are all familiar with those windmilling patterns used to illustrate fractals, with images reminiscent of the hippy era and psychedelic drugs.

Once I begin to seek out instances of recursion in the works of Borges, Google leads me down a rabbit hole of articles on Borges and the infinite, Borges and Buddhism, Borges and quantum mechanics, Borges and the multiverse, as well, of course, as better-known works on the writer, such as Guillermo Martínez’s study Borges and Mathematics. It is as if, for my sins, I have stepped inside the Library of Babel, given that the internet is the ultimate manifestation of that accursed and infinite library, and itself an unparalleled example of recursion. The Library of Babel has also been represented as a fractal, or a series of fractals, in the work of various artists, and the creators of one website – the babel image archives – uses images instead of letters of the alphabet to reproduce, as its creators claim, every image that ever has been or could be created within its chosen colour

palette.

Recursive Objects

In Martínez’s book there is much to give us pause for thought. Of particular note, in the first of his essays, is a reference to what he calls recursive objects: ‘It is possible to isolate this curious property of infinity and apply it to other objects or other situations in which a part of the object contains key information to the whole. We’ll call them recursive objects.’ For example, he reminds us that ‘from a biological point of view, a human being is a recursive object. A single human cell is enough to generate a clone [...] Certain mosaics are clearly recursive objects: in particular, those in which the design inherent in the first few tiles is repeated throughout.’ Martínez is a mathematician, as well as a novelist, and there is, among his various explanations – which we do not have time to go into now – an account of mathematical infinity in which it is shown that the whole is not necessarily greater than each of the parts: ‘There are certain parts that are as great as the whole. There are parts that are equivalent to the whole.’4

In the works of Borges, the supreme recursive objects are libraries and labyrinths. I have made reference to the Library of Babel – itself a labyrinth – and we know from various sources that the labyrinth was a foundational myth for young Georgie, as he was known by his family. In 1971 Borges was interviewed by the Economics Nobel laureate and renowned computer scientist Herbert Simon, one of the founding investigators of Artificial Intelligence, who was visiting Buenos Aires. This improbable meeting of minds was set up at Simon’s request. The conversation took place in English. In attendance, but not participating, was the writer Gabriel Zadunaisky, who recorded and translated the interview for the weekly journal Primera Plana.5 At the start of the interview, Simon asks Borges about the origins of his fascination with labyrinths, to which Borges replies that he could remember having seen an engraving of a labyrinth ‘in a French book’. Borges tells Simon that he used to gaze at this engraving of the labyrinth, and adds, a little ironically, that if he had had a magnifying glass, he might have been able to make out the shape of the Minotaur within its corridors. Simon, playing along, asks him if he ever found it, to which Borges replies, ‘As a matter of fact my eyesight was never very good’. And then, a little incongruously: ‘Later I discovered a little about life’s complexity, as if it were a game. I’m not talking about chess now.’ At least, this appears to be what he says. In the text published by Primera Plana, the words are ‘No me refiero al ajedrez en este caso’ (I’m not referring to chess here) but, bizarrely, in the Rodríguez Monegal biography (written in English) they become the exact opposite: ‘I’m talking about chess now’. There follows a passage in the interview in which Borges remarks on the play of words (in English) by which ‘maze’ is included within the word ‘amazement’, and he comments to Simon: ‘That’s the way that I regard life. A continuous amazement. A continuous bifurcation of the labyrinth.’6 I would ask you to hang on to this remark. We will return to it shortly.

Guillermo Martínez also reminds us that in Borges’s short parable ‘On Exactitude in Science’, there is another example of recursion, when the map of a single province occupies the space it was originally designed to represent, and with the years it falls apart, until its tattered ruins ‘are inhabited by animals and beggars’.7 Furthermore, Borges refers several times in his works to the map of Josiah Royce, a map which is perfectly traced on a small tract of English soil, and which is so precise that it contains within it a map of itself, which in turn contains a map of the map, and so on.

We might add to these examples the recursivity of A Thousand and One Nights that Borges references in both ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’ as well as in ‘When Fiction Lives in Fiction’. In this second text, as Borges reminds us, the murderous king appears to himself in one of the stories he is being told. To quote from the essay:

Incidentally, Julio Cortázar’s short story ‘The Continuity of Parks’ addresses the same notion, which is certainly no coincidence.

Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius

And so it is that I return to the origin, to the source of my enduring Borgesian adventure, re-reading the first of his stories that I encountered, ‘Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius’, in which Borges describes a fictional country, Uqbar, whose mythology originates from a mysterious world called Tlön. The story was first published in issue 68 of the magazine Sur, in May 1940, and contains a postscript, dated 1947, in which the reader learns that objects made in Uqbar have begun to make their way here, to ‘our’ world. The postscript also informs the reader that the author has reproduced the preceding article just as it appeared on its first publication in 1940, ‘omitting no more than some figures of speech, and a kind of burlesque summing up, which now strikes me as frivolous. So many things have happened since that date [...] I will confine myself to putting them down.’9 A curious opening, perhaps, to an impossible postscript, but what strikes the reader attentive to the notion of recursion is that, as Rodríguez Monegal has pointed out, ‘in the same way that the label of a tin of biscuits shows a picture of a tin of biscuits and so on, creating an infinite regression, Borges’ text was originally published in the sixty-eighth issue of Sur as a reproduction of a text already published in the sixty-eighth edition of Sur’.10

‘Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius’ marked a turning point in Borges’s evolution as a writer. First of all, the story stands as a melding together of the essayistic and the fictional, in a way that would become a staple of the writer’s work henceforth. And while the story’s form blurs the distinction between genres, the content veers towards fantastical or speculative fiction. And, significantly, there is a giveaway line near the start of the story that suggests its recursive and self-referential status: the story itself evolves out of a discussion Borges is having with Adolfo Bioy Casares about ‘a novel in the first person, whose narrator would omit or disfigure the facts and indulge in various contradictions which would permit a few readers – very few readers – to perceive an atrocious or banal reality’. We, the readers, might therefore deduce that this hypothetical novel is in fact the very story we are reading, and that the imaginary world is actually Earth – ‘Orbis Tertius’, as it was referred to in Renaissance cosmography.

As those who know the story will recall, Uqbar is a fictional place, originally conceived as a territory somewhere in Asia Minor, although this idea is quickly dropped. Tlön is presented first as a ‘region’, and then as a planet, which serves to provide the people of Uqbar with a mythology. All of the literature of Uqbar derives from or is set in Tlön. However, as we come to learn, the planet Tlön does not exist: it is a fiction within a fiction, a hoax that has been invented by a secret society founded by a millionaire, Ezra Buckley, in the nineteenth century. As a part of the hoax, stories about Tlön, and even some of its artefacts, have gradually been released into our world in an attempt to convince people of its reality. Putting it simply – and in terms that Borges himself might have avoided – Tlön is the unconscious of the fictitious country, Uqbar, its realm of myth and dream.

At one memorable point in the story, Borges describes one of the oldest regions of Tlön, in which it is a not uncommon occurrence for lost objects to be duplicated: ‘Two people are looking for a pencil; the first one finds it and says nothing; the second finds a second pencil, no less real, but more in keeping with his expectation. These secondary objects are called hrönir and, even though awkward in form, are a little larger than the originals. Until recently the hrönir were the accidental children of absentmindedness and forgetfulness.’

The search for the pencil results in two discoveries: in one of these, the pencil is the ‘authentic’ one that the protagonist lost, and in the other the pencil is a simulacrum (or hrön), a possible version of itself. This process of replication is repeated several times over, as Borges explains:

While Borges is clearly having a lot of fun with the erratic behaviour of his hrönir, there is also something disturbing about this incessant duplication of things, especially in the detail about those pencils, which reappear in a slightly different form from the versions that were lost. Are we to believe that all replication involves a divergence from the original? There is a vagueness, or a spectrality, even, that reminds one (since bits of Borges always remind one of other bits of Borges) of the indeterminacy possessed by various other objects in his work, from stones to tigers.

This, in part, is the subject of an unpublished essay by Kevin Wilson, titled ‘Of Stones and Tigers: Time, Infinity, Recursion and Liminality in the writings of JL Borges’. In this enterprising study, the author points to the enclosure in ‘The Circular Ruins’ that is described as being ‘crowned by the stone figure of a horse or tiger’; and the way, in ‘The Immortal’, that the city of the immortals appears to the protagonist as resembling ‘the body of a tiger or a bull pullulating with teeth, organs and heads monstrously yoked together yet hating each other’; or the way, in ‘Dreamtigers’, Borges tells us that his dreams have begun to yield, instead of a recognisable tiger, an approximate being, ‘looking more like a dog or a bird’. Isn’t it strange, in such a writer, otherwise so unequivocal, so exacting, so focused on clarity, that a tiger – the creature most hallowed in Borges’s personal mythology – should somehow be confounded with a horse, a bull, a dog or a bird? Unless, of course, that confusion is intentional, that it is a part of the point. But what is the point? That whatever is dreamed or willed is subject to external manipulation by forces unseen? That everything is an approximation of something else? That the pencil you hold in your hand might be simply the replica of another pencil lost in a contiguous world? That everything is an element in the infinite process of recursion?

Shortly after writing the above passage, I was due to teach a group of graduate students in the university where I work, and had intended to use ‘Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius’ as the text for that week’s seminar. The night before the class I dreamed that the story in my copy of the book differed in small but significant ways from the original, that it was in fact a hrön of the original story. In reality, I had bought my copy of the book, Fictions, many years before in a cheap edition, the cover of which displayed a badly drawn image of something midway between the Eye of Providence and a vagina. My copy of the story was a fake. I awoke in a state of anxiety, worried that I would not be able to retrieve the true story in time for my class. It was only later that I realised, of course, that my version was an English translation of Borges’s story, by Alastair Reid, and that all translations are, after a fashion, hrönir.

Borges ends the main part of his story, before embarking on his fallacious postscript, with an elegant passage summarising the process of recursion in Tlön:

Countless Worlds

As I have suggested, one of the things that first attracted me to Borges was his willingness to address the theme of the infinite permutations of chance. It is well known how often Borges referred to chance, whether in his stories, in his essays, or his poems. And long before I’d ever heard of parallel universes or the many worlds hypothesis, I was pretty much obsessed by the notion that every decision I took led to an outcome, or rather, a series of outcomes, which, had I chosen differently, would have led to different life circumstances, not just for me, but for others around me.

To use a footballing analogy, it used to bother me when a sports commentator would say ‘if he hadn’t missed that goal in the first half, the score would now be 2–1’. No! If he hadn’t missed that goal something else would have happened, and then something else; every moment of the game would have unfolded in a totally different way from the way it did by the missing or the scoring of the goal. Just as in life, to cite a few examples, what would have happened if I hadn’t stepped into the road in front of that car in Leytonstone in 1976; or, that night in July, 1984, if I hadn’t stayed on at the Café d’Artagnan for one more drink; or, if I had taken the bus rather than the metro on a particular night in Athens in 1986, the course of my life would no doubt have been different. True, the outcomes would often have been trivial, but they might, on the other hand, have been life-changing.

The term ‘sliding-door moment’ has become shorthand for this line of thinking, following the film of that name, starring Gwyneth Paltrow, but the concept itself is much older – and is, as we know, a staple in the fictions of Borges.

Hugh Everett, a Princeton PhD student, published a thesis in 1957 in which he claimed that we are living in a multiverse in which exist countless copies of each world’s contents, including ourselves. As Everett’s biographer, Peter Byrne, explains: ‘the wave function of an observer would, in effect, bifurcate at each interaction of the observer with a superposed object’. Thus every choice or decision in the course of a life precipitates the splitting of the universe, which then continues to split, infinitely, with each decisive turn that follows. As Byrne puts it: ‘Each branch has its own copy of the observer, a copy that perceived one of those alternatives as the outcome [...] each branch embarks on a different future, independently of the others.’14

At the time, Everett’s theory was rejected by the then reigning authority in quantum mechanics, Niels Bohr, and Everett, disgusted by academia, gave up theoretical physics and went to work for the Pentagon as a probability analyst, in which his work included the prediction of various scenarios of nuclear Armageddon. However, among a small group of followers, his hypothesis lived on, grew in momentum, and is now regarded by many of today’s leading quantum theorists as foundational. According to one of the most eminent of those physicists, Max Tegmark of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Everett’s discovery is ‘as important as Einstein’s work on relativity’.15

The idea that our world is one of many parallel worlds that branch off from each other, moment by moment, without intersecting or communicating, with the result that each permutation of every event has the potential to occur somewhere, is both appealing and terrifying. On a personal level, there is some comfort, to me at least, in imagining that all the bad decisions I ever took have – in some distant world – been counteracted by better ones. On the other hand, there is the moral dilemma of knowing that by making certain choices in this world, one runs the risk, almost by definition, of setting off a chain of events that will have negative ramifications elsewhere in the multiverse. After some consideration, however, one might come to the conclusion that the best way to live in a multiverse of many worlds is to be mindful of the way you live your life in this one.

The passage in Borges that has drawn comparisons with Everett’s hypothesis occurs in ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’. In this story, which takes place in England during the First World War, the protagonist, Yu Tsun, is working for the Germans as a spy. Yu Tsun, who is Chinese (and who despises Germany as a ‘barbarous country’) is being pursued by a British agent named Richard Madden, who is in fact Irish, a detail – reflecting those that besiege Yu Tsun himself – that already suggests divided loyalties. Yu Tsun has information of great importance to the German war effort, but with Madden closing in on him, is unable to pass this on to his masters in Berlin (nor do we, the readers, learn what this information consists of until the final paragraph). He goes, inexplicably, as it seems at first, to the house of Dr Stephen Albert, a renowned Sinologist with a special research interest in Ts’ui Pên, Tsun’s grandfather, a respected sage, who retired as Governor of Yunnan Province in order to write a vast novel and to create a maze ‘in which all men would lose themselves’. He spent thirteen years absorbed in these tasks before he was assassinated by a stranger. His novel had no sense to it and nobody ever found his labyrinth. It turns out, this being Borges, that the book and the labyrinth were one and the same thing, and the title of this infinite and chaotic novel is, of course, ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’.

Albert tells Yu Tsun that Ts’ui Pên’s novel is modelled on a labyrinth in the sense that it constantly bifurcates in time, but not in space. ‘In all fiction,’ he explains, ‘when a man is faced with alternatives he chooses one at the expense of the others.’ However, in this novel, whenever a course of action has to be decided upon, rather than choosing one and pursuing its linear development, each course taken divides in two, with each of these being the point of departure for other, further, bifurcations, and so on. As Dr Albert explains:

And before we become too overawed by Borges’s apparent act of precognition, it should be noted, following Dominic Moran, in an essay titled ‘Borges and the Multiverse’ (2012), that there is clear evidence that Borges borrowed (or plagiarised) key features of his story from the English science fiction writer Olaf Stapledon (1886–1950) – most notably from his novel Star Maker (1937) – as well as from a famous Chinese novel translated into English as The Dream of the Red Chamber, both of which Borges had reviewed in the Argentine magazine El Hogar in November 1937. Not only this, but, as Moran eloquently asserts:

Whether or not Borges knew of the theories of quantum mechanics is addressed quite specifically in a short article by the physicist Alberto G. Rojo, who fell into conversation with the author on 9 July 1985, and asked him whether he knew that his work was referenced in the work of several notable physicists. Borges’s answer is revealing: ‘How strange! This is really curious because the only thing I know about physics comes from my father, who once showed me how a barometer works.’ ‘He said it,’ Rojo, tells us, ‘with an oriental modesty, moving his hands as though trying to draw the apparatus in the air. And then he added: “Physicists are so imaginative!”’19

In Rojo’s opinion, the similarity between the two texts just cited indicates ‘the extraordinary way Borges’s mind was immersed in the cultural matrix of the twentieth century, in that complex web whose secret components ramify beyond the demarcations between disciplines [...] While Everett’s [...] ideas can be read as science fiction, in ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’, fiction can be read as science.’

In the documentary film Parallel Worlds, Parallel Lives, Hugh Everett’s son, Mark, who happens to be lead singer for the rock band The Eels, travels across the United States in search of the father he barely knew. The story is both informative and moving. As has been noted, Hugh Everett's theories were rejected in his lifetime, and he ended up a rather miserable and lonely man, consumed by a sense of loss and sinking into alcoholism, a state no doubt exacerbated by the apocalyptic tedium of the work he carried as an analyst for the Pentagon. There is something essentially Borgesian about the son’s quest for his father – the man who devised the single most astonishing theory of quantum mechanics – and his recognition of similarities between the two of them; and in an especially poignant section of the film, he reveals, in the cellar of his home, boxes and boxes filled with his father’s notebooks. Watching the documentary, it is as if Ts’ui Pên’s labyrinth has at last been tracked down in the basement of this mildly eccentric and self-effacing musician.

Earlier I referred to the Proustian notion that remembering a particular episode from one’s own life is nothing less than a recursive projection of oneself out of the present. And so it is that the association of my first encounter with the stories of Borges amid the landscape of Crete, with its rugged mountains and its wine-dark sea, is indissoluble.

Reading outside my stone cabin at sunset, I heard an exchange of voices. In the distance, some way above me, a man and a woman were calling to each other, each voice lifting with a strange buoyancy across the gorge that lay between one flank of the mountain and the next. Only the nearer figure, the man, was visible, and his voice seemed to rebound off the wall of the chasm, half a mile away. The woman remained out of sight, but her voice likewise drifted across the gorge, with an ethereal vibrancy. There were perhaps a dozen turns, and then silence. I listened, spellbound. And that brief exchange, that shouted conversation, with its unearthly sounds, the tension between the voices, the exhalations and long vowels echoing off the sides of the mountain, would haunt me for years, haunts me still.

They seemed to me to be speaking across time, that man and woman. Their ancestors, or other versions of themselves, had been having that conversation, exchanging those same sounds, that same music, across countless centuries. It was, for me, a lesson in both the durability and at the same time the fragility of our lives; that conversation, that calling across the chasm, represented a glimpse of eternity. And with this I am reminded that in ‘The History of Eternity’ Borges wrote of the idea of the infinite that it ‘liberates us, even if for only a few moments, from the unbearable oppression of the passage of time’. In the interview with Herbert Simon, Borges utters the phrase I asked you to bear in mind: ‘That’s the way I regard life. A continuous amazement. A continuous bifurcation of the labyrinth.’ Which in some way leads us back, in recursive fashion, to where we started, with Borges claiming that he could trace his first notion of the problem of infinity to that far distant biscuit tin.

But the moment passed, and continues to pass, lives on in my memory and imagination, and in so many memories that are the projections of myself out of the present, reminding us that of all the possible lives that each of us might live, we have this one, linked by an invisible thread to the innumerable lives that are unlived by us, but which – who knows – are even now being lived out by another version of ourselves in some other garden of forking paths. And having returned once more to that other, earlier life, I have ensured that this paper becomes an exercise in recursion in which I, the narrator, remember a previous self who wrote an article that recalls a stone cabin beneath a mountain where an even earlier version of that narrator discovers, for the first time, the stories of Jorge Luis Borges.

This childhood experience of Borges’s, in turn, evokes the vertigo the reader might feel before the various mysteries and labyrinths, the doublings and redoublings, and the recursive modes of narration that populate so many of the author’s stories. And it is this notion of recursion (or recurrent self-referentiality) that I wish to address and explore today.

Of course, I don’t know what biscuit tin Borges had in mind, but I definitely remember this one, from my own childhood, which, like his, contains on the lid an image of itself, and within that image another, and so on ad infinitum. Like the young Borges, I remember being enthralled by the image.

A dozen or so years ago I was invited by the Argentine newspaper Clarín to write a piece commemorating the twenty-fifth anniversary of Borges’s death. At around the same time, as chance would have it, I wrote a piece for the British newspaper the Independent for their series ‘Book of a Lifetime’, in which writers were invited to contribute short summaries of a favourite book. I chose Borges’s Fictions, and claimed that ‘other books have had a powerful impact on me, but none marked a turning-point in my understanding of the world and the written word in quite the same way’. In both articles I began by describing the circumstances in which I was living when I first came across the work of the Argentine author, more or less as I record them here.

I discovered Borges’s short stories at the age of eighteen, when I was living in an abandoned shepherd’s hut at the foot of a mountain named Keratókambos, on the island of Crete. I found the place while exploring a deserted stretch of the south coast of the island, and moved in for the summer. I had a few books with me;

I had just devoured The Brothers Karamazov and The Magic Mountain in rapid succession, and the brevity and intensity of Borges’s writing came as a revelation. Borges himself had something to say about big novels, as he articulated in the Prologue to Ficciones (1944): ‘The composition of vast books is a laborious and impoverishing extravagance. To go on for five hundred pages developing an idea whose perfect oral exposition is possible in a few minutes! A better course of procedure is to pretend that these books exist and then to offer a résumé, a commentary.’2 The idea that instead of writing voluminous books we can simply pretend that they exist had a profound appeal to the budding writer in me, horrified at the interminable exposition of those mighty tomes by Dostoyevsky and Mann. Borges’s ludic style and brevity were much more attractive, and there was something enormously liberating, a kind of weightlessness, to the idea that by minimising the word count we might invoke extraordinary worlds without having to set them down with wearisome description, endless exposition and fatuous dialogue. If only things were so simple. The brevity of a literary work does not diminish its complexity, and the worlds one encounters in Borges’s compact stories contain multitudes.

Fiction within Fiction

But more than anything else, all those years ago, I was seduced by the idea that every instant contains the potential for an infinity of outcomes – a recurring motif in Borges’s work – or that our universe is only one in a multiplicity of possible universes; or, less appealingly, that rather than being the proprietors of our own consciousness, we are being dreamed by some other entity. These are not comfortable ideas to live with, pushing, as they do, at the edges of comprehension. Always dissatisfied with received wisdoms, these ideas took a hold on me early in life, and I have never abandoned them, nor felt inclined to do so.

Borges concludes his essay on ‘When Fiction Lives in Fiction’ with a summary of Flann O’Brien’s novel At Swim-Two-Birds (which, it might be noted, he reviewed in the magazine El Hogar only six months after it first appeared in English), in which a young student from Dublin writes a novel about a publican from that city, who in turn writes a novel about his customers, one of whom is the student author; and he quotes Schopenhauer’s comment, ‘that dreaming and wakefulness are the pages of a single book, and that to read them in order is to live, and to leaf through them at random, to dream. Paintings within paintings and books that branch off into other books help us sense this oneness.’ In other words, the perspective that one story was a vehicle for other stories, and that the process could become one of unlimited recursion, was established quite early in the writer’s career, and over time it became a hallmark of his literary oeuvre.

A fundamental principle within the study of linguistics is that, in spoken language, an idea can be contained within an idea, a phrase within a phrase. This forms the basis of recursion in grammar. Noam Chomsky has claimed that it is the essential tool that underlies all of the creativity of human language. In theory, according to Chomsky, an infinitely long, recursive sentence is possible, since there is no limit to the mind’s capacity to embed one thought within another. Our language is recursive because our minds are recursive.

A parody of the opening sentence of a now-forgotten novel, Paul Clifford, by the nineteenth-century English novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton, might serve as an initial illustration of recursion – ‘It was a dark and stormy night, and we said to the captain: “Tell us a story!” And this is the story the captain told: “It was a dark and stormy night, and we said to the captain, ‘Tell us a story!’ And this is the story the captain told: ‘It was a dark and stormy night ”’’...

Another exercise in recursion would be the English nursery rhyme about an old lady who swallows a fly, which, as the song’s chorus repeats, ‘wriggled and jiggled and tickled inside her’. The unfortunate woman decides to swallow a spider in order to catch the fly, and then successively, a bird to catch the spider, a cat to catch the bird, a dog to catch the cat, and so on in a theoretically infinite number of permutations. This gruesome little song neatly exemplifies the nature of recursion and, as I discovered, is even used as an illustration in a computer science programming manual on that topic. An article on recursive thinking in American Scientist points out that the realisation that one has thoughts about one’s own thoughts itself constitutes a theory of mind.3 René Descartes is renowned for the phrase cogito, ergo sum (although he actually wrote ‘je pense, donc je suis’: I think, therefore I am). Descartes presented this utterance as proof of his own existence, and although he sometimes doubted it, the doubt was itself a mode of thinking, so his real existence was not in doubt. The phrase is fundamentally recursive, since it involves not only thinking, but thinking about thinking.

Remembering a particular episode from one’s own life suggests a recursive projection of oneself out of the present moment. In the novel À la recherche du temps perdu, Marcel Proust returns to various projections of episodic memory, including the famous moment when the taste of a petite madeleine evokes the memory of a past event in the narrator’s mind. In terms of the present text, we might consider as recursive the references I made a few moments ago, when I said that I started an article in Clarín twelve years ago with (almost) the same words that I used today, or when I recited the words: ‘All those years ago, I was seduced by the idea that every instant contains the potential for an infinity of outcomes.’

The notion of recursion is also the driving force behind fractals, complex patterns that are self-replicating across different scales. Fractals are created by repeating a simple process over and over in an ongoing feedback loop. It has been claimed that the coast of Brittany has the characteristics of a fractal, for example, and we are all familiar with those windmilling patterns used to illustrate fractals, with images reminiscent of the hippy era and psychedelic drugs.

Once I begin to seek out instances of recursion in the works of Borges, Google leads me down a rabbit hole of articles on Borges and the infinite, Borges and Buddhism, Borges and quantum mechanics, Borges and the multiverse, as well, of course, as better-known works on the writer, such as Guillermo Martínez’s study Borges and Mathematics. It is as if, for my sins, I have stepped inside the Library of Babel, given that the internet is the ultimate manifestation of that accursed and infinite library, and itself an unparalleled example of recursion. The Library of Babel has also been represented as a fractal, or a series of fractals, in the work of various artists, and the creators of one website – the babel image archives – uses images instead of letters of the alphabet to reproduce, as its creators claim, every image that ever has been or could be created within its chosen colour

palette.

Recursive Objects

In Martínez’s book there is much to give us pause for thought. Of particular note, in the first of his essays, is a reference to what he calls recursive objects: ‘It is possible to isolate this curious property of infinity and apply it to other objects or other situations in which a part of the object contains key information to the whole. We’ll call them recursive objects.’ For example, he reminds us that ‘from a biological point of view, a human being is a recursive object. A single human cell is enough to generate a clone [...] Certain mosaics are clearly recursive objects: in particular, those in which the design inherent in the first few tiles is repeated throughout.’ Martínez is a mathematician, as well as a novelist, and there is, among his various explanations – which we do not have time to go into now – an account of mathematical infinity in which it is shown that the whole is not necessarily greater than each of the parts: ‘There are certain parts that are as great as the whole. There are parts that are equivalent to the whole.’4

In the works of Borges, the supreme recursive objects are libraries and labyrinths. I have made reference to the Library of Babel – itself a labyrinth – and we know from various sources that the labyrinth was a foundational myth for young Georgie, as he was known by his family. In 1971 Borges was interviewed by the Economics Nobel laureate and renowned computer scientist Herbert Simon, one of the founding investigators of Artificial Intelligence, who was visiting Buenos Aires. This improbable meeting of minds was set up at Simon’s request. The conversation took place in English. In attendance, but not participating, was the writer Gabriel Zadunaisky, who recorded and translated the interview for the weekly journal Primera Plana.5 At the start of the interview, Simon asks Borges about the origins of his fascination with labyrinths, to which Borges replies that he could remember having seen an engraving of a labyrinth ‘in a French book’. Borges tells Simon that he used to gaze at this engraving of the labyrinth, and adds, a little ironically, that if he had had a magnifying glass, he might have been able to make out the shape of the Minotaur within its corridors. Simon, playing along, asks him if he ever found it, to which Borges replies, ‘As a matter of fact my eyesight was never very good’. And then, a little incongruously: ‘Later I discovered a little about life’s complexity, as if it were a game. I’m not talking about chess now.’ At least, this appears to be what he says. In the text published by Primera Plana, the words are ‘No me refiero al ajedrez en este caso’ (I’m not referring to chess here) but, bizarrely, in the Rodríguez Monegal biography (written in English) they become the exact opposite: ‘I’m talking about chess now’. There follows a passage in the interview in which Borges remarks on the play of words (in English) by which ‘maze’ is included within the word ‘amazement’, and he comments to Simon: ‘That’s the way that I regard life. A continuous amazement. A continuous bifurcation of the labyrinth.’6 I would ask you to hang on to this remark. We will return to it shortly.

Guillermo Martínez also reminds us that in Borges’s short parable ‘On Exactitude in Science’, there is another example of recursion, when the map of a single province occupies the space it was originally designed to represent, and with the years it falls apart, until its tattered ruins ‘are inhabited by animals and beggars’.7 Furthermore, Borges refers several times in his works to the map of Josiah Royce, a map which is perfectly traced on a small tract of English soil, and which is so precise that it contains within it a map of itself, which in turn contains a map of the map, and so on.

We might add to these examples the recursivity of A Thousand and One Nights that Borges references in both ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’ as well as in ‘When Fiction Lives in Fiction’. In this second text, as Borges reminds us, the murderous king appears to himself in one of the stories he is being told. To quote from the essay:

None of them is as disturbing as that of night 602, a piece of magic among the nights. On that strange night, the king hears his own story from the queen’s lips. He hears the beginning of the story, which includes all the others, and also – monstrously – itself. Does the reader have a clear sense of the vast possibility held out by this interpolation, its peculiar danger? Were the queen to persist, the immobile king would forever listen to the truncated story of the thousand and one nights, now infinite and circular [...] In The Thousand and One Nights, Scheherazade tells many stories; one of them is, almost, the story of The Thousand and One Nights.8

Incidentally, Julio Cortázar’s short story ‘The Continuity of Parks’ addresses the same notion, which is certainly no coincidence.

Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius

And so it is that I return to the origin, to the source of my enduring Borgesian adventure, re-reading the first of his stories that I encountered, ‘Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius’, in which Borges describes a fictional country, Uqbar, whose mythology originates from a mysterious world called Tlön. The story was first published in issue 68 of the magazine Sur, in May 1940, and contains a postscript, dated 1947, in which the reader learns that objects made in Uqbar have begun to make their way here, to ‘our’ world. The postscript also informs the reader that the author has reproduced the preceding article just as it appeared on its first publication in 1940, ‘omitting no more than some figures of speech, and a kind of burlesque summing up, which now strikes me as frivolous. So many things have happened since that date [...] I will confine myself to putting them down.’9 A curious opening, perhaps, to an impossible postscript, but what strikes the reader attentive to the notion of recursion is that, as Rodríguez Monegal has pointed out, ‘in the same way that the label of a tin of biscuits shows a picture of a tin of biscuits and so on, creating an infinite regression, Borges’ text was originally published in the sixty-eighth issue of Sur as a reproduction of a text already published in the sixty-eighth edition of Sur’.10

‘Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius’ marked a turning point in Borges’s evolution as a writer. First of all, the story stands as a melding together of the essayistic and the fictional, in a way that would become a staple of the writer’s work henceforth. And while the story’s form blurs the distinction between genres, the content veers towards fantastical or speculative fiction. And, significantly, there is a giveaway line near the start of the story that suggests its recursive and self-referential status: the story itself evolves out of a discussion Borges is having with Adolfo Bioy Casares about ‘a novel in the first person, whose narrator would omit or disfigure the facts and indulge in various contradictions which would permit a few readers – very few readers – to perceive an atrocious or banal reality’. We, the readers, might therefore deduce that this hypothetical novel is in fact the very story we are reading, and that the imaginary world is actually Earth – ‘Orbis Tertius’, as it was referred to in Renaissance cosmography.

As those who know the story will recall, Uqbar is a fictional place, originally conceived as a territory somewhere in Asia Minor, although this idea is quickly dropped. Tlön is presented first as a ‘region’, and then as a planet, which serves to provide the people of Uqbar with a mythology. All of the literature of Uqbar derives from or is set in Tlön. However, as we come to learn, the planet Tlön does not exist: it is a fiction within a fiction, a hoax that has been invented by a secret society founded by a millionaire, Ezra Buckley, in the nineteenth century. As a part of the hoax, stories about Tlön, and even some of its artefacts, have gradually been released into our world in an attempt to convince people of its reality. Putting it simply – and in terms that Borges himself might have avoided – Tlön is the unconscious of the fictitious country, Uqbar, its realm of myth and dream.

At one memorable point in the story, Borges describes one of the oldest regions of Tlön, in which it is a not uncommon occurrence for lost objects to be duplicated: ‘Two people are looking for a pencil; the first one finds it and says nothing; the second finds a second pencil, no less real, but more in keeping with his expectation. These secondary objects are called hrönir and, even though awkward in form, are a little larger than the originals. Until recently the hrönir were the accidental children of absentmindedness and forgetfulness.’

The search for the pencil results in two discoveries: in one of these, the pencil is the ‘authentic’ one that the protagonist lost, and in the other the pencil is a simulacrum (or hrön), a possible version of itself. This process of replication is repeated several times over, as Borges explains:

[T]he hrönir of the second and third degree – that is, the hrönir derived from another hrön, and the hrönir derived from the hrön of a hrön – exaggerate the flaws of the original; those of the fifth degree are almost uniform; those of the ninth can be confused with those of the second; and those of the eleventh degree have a purity of form which the originals do not possess. The process is a recurrent one; a hrön of the twelfth degree begins to deteriorate in quality. Stranger and more perfect than any hrön is sometimes the ur, which is a thing produced by suggestion, an object brought into being by hope. The great gold mask I mentioned previously is a distinguished example.11It seems likely that Borges took the word hrön from the almost identical Icelandic hrönn (plural hrannier), meaning ‘wave’. Alongside the connotations of continuous movement, re-shaping and re-formulation associated with waves in the sea, we might note that the term ‘wave function’, as defined by Schrödinger in 1928, has a distinct meaning in quantum mechanics, namely that ‘a wave function is defined as a function describing the probability of a particle’s quantum state as a function of position, momentum, time, and/or spin.’12 I do not know whether Borges was familiar with wave function theory in 1940. If he was, then he was making a private joke detectable to only a few – very few – readers, but if he did not, his selection of the word ‘hrön’ to define something in a state of almost constant change was remarkably prescient.

While Borges is clearly having a lot of fun with the erratic behaviour of his hrönir, there is also something disturbing about this incessant duplication of things, especially in the detail about those pencils, which reappear in a slightly different form from the versions that were lost. Are we to believe that all replication involves a divergence from the original? There is a vagueness, or a spectrality, even, that reminds one (since bits of Borges always remind one of other bits of Borges) of the indeterminacy possessed by various other objects in his work, from stones to tigers.

This, in part, is the subject of an unpublished essay by Kevin Wilson, titled ‘Of Stones and Tigers: Time, Infinity, Recursion and Liminality in the writings of JL Borges’. In this enterprising study, the author points to the enclosure in ‘The Circular Ruins’ that is described as being ‘crowned by the stone figure of a horse or tiger’; and the way, in ‘The Immortal’, that the city of the immortals appears to the protagonist as resembling ‘the body of a tiger or a bull pullulating with teeth, organs and heads monstrously yoked together yet hating each other’; or the way, in ‘Dreamtigers’, Borges tells us that his dreams have begun to yield, instead of a recognisable tiger, an approximate being, ‘looking more like a dog or a bird’. Isn’t it strange, in such a writer, otherwise so unequivocal, so exacting, so focused on clarity, that a tiger – the creature most hallowed in Borges’s personal mythology – should somehow be confounded with a horse, a bull, a dog or a bird? Unless, of course, that confusion is intentional, that it is a part of the point. But what is the point? That whatever is dreamed or willed is subject to external manipulation by forces unseen? That everything is an approximation of something else? That the pencil you hold in your hand might be simply the replica of another pencil lost in a contiguous world? That everything is an element in the infinite process of recursion?

Shortly after writing the above passage, I was due to teach a group of graduate students in the university where I work, and had intended to use ‘Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius’ as the text for that week’s seminar. The night before the class I dreamed that the story in my copy of the book differed in small but significant ways from the original, that it was in fact a hrön of the original story. In reality, I had bought my copy of the book, Fictions, many years before in a cheap edition, the cover of which displayed a badly drawn image of something midway between the Eye of Providence and a vagina. My copy of the story was a fake. I awoke in a state of anxiety, worried that I would not be able to retrieve the true story in time for my class. It was only later that I realised, of course, that my version was an English translation of Borges’s story, by Alastair Reid, and that all translations are, after a fashion, hrönir.

Borges ends the main part of his story, before embarking on his fallacious postscript, with an elegant passage summarising the process of recursion in Tlön:

Things duplicate themselves in Tlön. They tend at the same time to efface themselves, to lose their detail when people forget them. The classic example is that of a stone threshold which lasted as long as it was visited by a beggar, and which faded from sight on his death. Occasionally, a few birds, a horse perhaps, have saved the ruins of an amphitheatre.13If I might be permitted a further biographical intrusion: the phrase ‘un umbral que perduró mientras lo visitaba un mendigo’ (a threshold which lasted as long as it was visited by a beggar) evokes the stone hut in which I was living when I read the story (in the original it is simply an ‘umbral’ – threshold – whereas in the English translation by Alastair Reid, it is rendered as ‘stone threshold’, reminding us, obliquely, of Borges’s famous collocation, in ‘Borges and I’, of ‘stones and tigers’). At one point during that summer of 1975, I had to travel to the island’s capital, Iraklion, to pick up mail. On returning to the cabin I found, to my surprise, that someone had paid a visit during my absence. Lying beside the open entrance to the hut was a bottle of the local home distilled spirit, tsikoudia, and a small box of loukoumi (Turkish delight) wrapped in a coarse ribbon. I was confused as to who might have left such a gift. The mystery was resolved a few days later when a lithe, elderly Cretan appeared as I sat reading – as was my habit – at the hut’s threshold. He was, he told me, the owner of the place, but he had no use for it any more. He had noticed some time ago that I had moved in, and was curious to meet me. I could, he said, stay for as long as I wished. I brewed coffee and conversed with him in my pidgin Greek, illustrated with much gesticulation and mime. He was a perfect gentleman, this elderly Cretan from the days before tourism laid waste to the country: enigmatic, generous, gifted with a subtle sense of humour, he accepted my occupancy of the hut as an act of providence. He seemed pleased that I was there. In a sense, I was carrying out the function of the beggar in Borges’s story: for my host, perhaps, the hut only had purpose (or reality) for as long as someone lived in it.

Countless Worlds

As I have suggested, one of the things that first attracted me to Borges was his willingness to address the theme of the infinite permutations of chance. It is well known how often Borges referred to chance, whether in his stories, in his essays, or his poems. And long before I’d ever heard of parallel universes or the many worlds hypothesis, I was pretty much obsessed by the notion that every decision I took led to an outcome, or rather, a series of outcomes, which, had I chosen differently, would have led to different life circumstances, not just for me, but for others around me.

To use a footballing analogy, it used to bother me when a sports commentator would say ‘if he hadn’t missed that goal in the first half, the score would now be 2–1’. No! If he hadn’t missed that goal something else would have happened, and then something else; every moment of the game would have unfolded in a totally different way from the way it did by the missing or the scoring of the goal. Just as in life, to cite a few examples, what would have happened if I hadn’t stepped into the road in front of that car in Leytonstone in 1976; or, that night in July, 1984, if I hadn’t stayed on at the Café d’Artagnan for one more drink; or, if I had taken the bus rather than the metro on a particular night in Athens in 1986, the course of my life would no doubt have been different. True, the outcomes would often have been trivial, but they might, on the other hand, have been life-changing.

The term ‘sliding-door moment’ has become shorthand for this line of thinking, following the film of that name, starring Gwyneth Paltrow, but the concept itself is much older – and is, as we know, a staple in the fictions of Borges.

Hugh Everett, a Princeton PhD student, published a thesis in 1957 in which he claimed that we are living in a multiverse in which exist countless copies of each world’s contents, including ourselves. As Everett’s biographer, Peter Byrne, explains: ‘the wave function of an observer would, in effect, bifurcate at each interaction of the observer with a superposed object’. Thus every choice or decision in the course of a life precipitates the splitting of the universe, which then continues to split, infinitely, with each decisive turn that follows. As Byrne puts it: ‘Each branch has its own copy of the observer, a copy that perceived one of those alternatives as the outcome [...] each branch embarks on a different future, independently of the others.’14

At the time, Everett’s theory was rejected by the then reigning authority in quantum mechanics, Niels Bohr, and Everett, disgusted by academia, gave up theoretical physics and went to work for the Pentagon as a probability analyst, in which his work included the prediction of various scenarios of nuclear Armageddon. However, among a small group of followers, his hypothesis lived on, grew in momentum, and is now regarded by many of today’s leading quantum theorists as foundational. According to one of the most eminent of those physicists, Max Tegmark of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Everett’s discovery is ‘as important as Einstein’s work on relativity’.15

The idea that our world is one of many parallel worlds that branch off from each other, moment by moment, without intersecting or communicating, with the result that each permutation of every event has the potential to occur somewhere, is both appealing and terrifying. On a personal level, there is some comfort, to me at least, in imagining that all the bad decisions I ever took have – in some distant world – been counteracted by better ones. On the other hand, there is the moral dilemma of knowing that by making certain choices in this world, one runs the risk, almost by definition, of setting off a chain of events that will have negative ramifications elsewhere in the multiverse. After some consideration, however, one might come to the conclusion that the best way to live in a multiverse of many worlds is to be mindful of the way you live your life in this one.

The passage in Borges that has drawn comparisons with Everett’s hypothesis occurs in ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’. In this story, which takes place in England during the First World War, the protagonist, Yu Tsun, is working for the Germans as a spy. Yu Tsun, who is Chinese (and who despises Germany as a ‘barbarous country’) is being pursued by a British agent named Richard Madden, who is in fact Irish, a detail – reflecting those that besiege Yu Tsun himself – that already suggests divided loyalties. Yu Tsun has information of great importance to the German war effort, but with Madden closing in on him, is unable to pass this on to his masters in Berlin (nor do we, the readers, learn what this information consists of until the final paragraph). He goes, inexplicably, as it seems at first, to the house of Dr Stephen Albert, a renowned Sinologist with a special research interest in Ts’ui Pên, Tsun’s grandfather, a respected sage, who retired as Governor of Yunnan Province in order to write a vast novel and to create a maze ‘in which all men would lose themselves’. He spent thirteen years absorbed in these tasks before he was assassinated by a stranger. His novel had no sense to it and nobody ever found his labyrinth. It turns out, this being Borges, that the book and the labyrinth were one and the same thing, and the title of this infinite and chaotic novel is, of course, ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’.

Albert tells Yu Tsun that Ts’ui Pên’s novel is modelled on a labyrinth in the sense that it constantly bifurcates in time, but not in space. ‘In all fiction,’ he explains, ‘when a man is faced with alternatives he chooses one at the expense of the others.’ However, in this novel, whenever a course of action has to be decided upon, rather than choosing one and pursuing its linear development, each course taken divides in two, with each of these being the point of departure for other, further, bifurcations, and so on. As Dr Albert explains:

Your ancestor [...] believed in an infinite series of times, in a dizzily growing, ever-spreading network of diverging, converging and parallel times. This web of time – the strands of which approach one another, bifurcate, intersect, or ignore each other through the centuries – embraces every possibility. We do not exist in most of them. In some you exist and not I, while in others I do, and you do not, and in yet others both of us exist. In this one, in which chance has favoured me, you have come to my gate. In another, you, crossing the garden, have found me dead. In yet another, I say these very same words, but am an error, a phantom.After this brief elaboration on the nature of the multiverse, it almost comes as an anti-climax to learn that the only reason Yu Tsun has decided to come to this house is to murder Albert, whose name will be plastered all over the newspapers the following day, thereby informing Yu Tsun’s spy chief in Berlin that Albert is the name of the French town from which the Allies are preparing a massive artillery offensive against the German lines. As others have remarked, the ‘pullulation of possibilities’ that Yu Tsun senses anticipates the many worlds hypothesis of the quantum physicist Hugh Everett by fifteen years. The similarities between Everett’s hypothesis and Borges’s story are encapsulated in corresponding passages from each work. In the fifth section of Everett’s original article, we find:

‘In all of them,’ I enunciated, with a tremor in my voice, ‘I deeply appreciate and am grateful for the restoration of Ts’ui Pên’s garden.’

‘Not in all,’ he murmured with a smile. ‘Time is forever dividing itself towards innumerable futures and in one of them you are my enemy.’

Once again I sensed the pullulation of which

I have already spoken. It seemed to me that the dew-damp garden surrounding the house was infinitely saturated with invisible people. All were Albert and myself, secretive, busy and multiform in other dimensions of time.

I lifted my eyes and the short nightmare disappeared.16

The ‘trajectory’ of the memory configuration of an observer performing a sequence of measurements is [...] not a linear sequence of memory configurations, but a branching tree, with all possible outcomes existing simultaneously.17And in Borges’s story:

In all fiction, when a man is faced with alternatives he chooses one at the expense of the others. In the almost unfathomable Ts’ui Pên, he chooses – simultaneously – all of them. He thus creates various futures, various times that start others that will in their turn branch out and bifurcate in other times.Daniel Balderstone, in his book How Borges Wrote, states that Borges’s tendency ‘to write with numerous variations and possibilities in mind, adding layers by accretion, then re-writing several more times [...] means that his creative process involved the weaving together of textual fragments into provisional, not definitive wholes. It is almost,’ he continues, ‘as though Borges were enacting his own version of the many worlds theory in his writing practice.’ Elsewhere, Balderstone comments that ‘[t]hese reflections on myriad possibilities, in manuscripts that are themselves vast semantic fields of possibilities, show that Borges worked out on the page the formal features of his linguistic games with some precision, leaving hints of this process in the final texts. What historians of science have noticed as an early version of the “many worlds hypothesis” is of a piece with Borges’ poetics of prose, itself a literary corollary of the uncertainty principle.’ But if this is the case, I would venture, Borges is by no means alone in such practices.

And before we become too overawed by Borges’s apparent act of precognition, it should be noted, following Dominic Moran, in an essay titled ‘Borges and the Multiverse’ (2012), that there is clear evidence that Borges borrowed (or plagiarised) key features of his story from the English science fiction writer Olaf Stapledon (1886–1950) – most notably from his novel Star Maker (1937) – as well as from a famous Chinese novel translated into English as The Dream of the Red Chamber, both of which Borges had reviewed in the Argentine magazine El Hogar in November 1937. Not only this, but, as Moran eloquently asserts:

Regarding the question of Borges’ (or rather Stapledon’s) clairvoyance, it might be remarked that if Everett’s theory or some refinement of it turns out to be true, then it was inevitable that not just in one but in countless universes ‘Borges’, or some version of him, should have written a story prior to the emergence of the theory, just as it was inevitable that in countless others still ‘he’ or one of his avatars [...] should have written innumerable versions which differ by a comma, a full stop, a letter, a word etcParallel Worlds, Parallel Lives

(I could go on – endlessly) from the one that we have. In other words – and this is one of the bizarre but strictly logical consequences of a multiverse in which anything can happen – he deserves absolutely no credit for it.18

Whether or not Borges knew of the theories of quantum mechanics is addressed quite specifically in a short article by the physicist Alberto G. Rojo, who fell into conversation with the author on 9 July 1985, and asked him whether he knew that his work was referenced in the work of several notable physicists. Borges’s answer is revealing: ‘How strange! This is really curious because the only thing I know about physics comes from my father, who once showed me how a barometer works.’ ‘He said it,’ Rojo, tells us, ‘with an oriental modesty, moving his hands as though trying to draw the apparatus in the air. And then he added: “Physicists are so imaginative!”’19

In Rojo’s opinion, the similarity between the two texts just cited indicates ‘the extraordinary way Borges’s mind was immersed in the cultural matrix of the twentieth century, in that complex web whose secret components ramify beyond the demarcations between disciplines [...] While Everett’s [...] ideas can be read as science fiction, in ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’, fiction can be read as science.’

In the documentary film Parallel Worlds, Parallel Lives, Hugh Everett’s son, Mark, who happens to be lead singer for the rock band The Eels, travels across the United States in search of the father he barely knew. The story is both informative and moving. As has been noted, Hugh Everett's theories were rejected in his lifetime, and he ended up a rather miserable and lonely man, consumed by a sense of loss and sinking into alcoholism, a state no doubt exacerbated by the apocalyptic tedium of the work he carried as an analyst for the Pentagon. There is something essentially Borgesian about the son’s quest for his father – the man who devised the single most astonishing theory of quantum mechanics – and his recognition of similarities between the two of them; and in an especially poignant section of the film, he reveals, in the cellar of his home, boxes and boxes filled with his father’s notebooks. Watching the documentary, it is as if Ts’ui Pên’s labyrinth has at last been tracked down in the basement of this mildly eccentric and self-effacing musician.

Earlier I referred to the Proustian notion that remembering a particular episode from one’s own life is nothing less than a recursive projection of oneself out of the present. And so it is that the association of my first encounter with the stories of Borges amid the landscape of Crete, with its rugged mountains and its wine-dark sea, is indissoluble.

Reading outside my stone cabin at sunset, I heard an exchange of voices. In the distance, some way above me, a man and a woman were calling to each other, each voice lifting with a strange buoyancy across the gorge that lay between one flank of the mountain and the next. Only the nearer figure, the man, was visible, and his voice seemed to rebound off the wall of the chasm, half a mile away. The woman remained out of sight, but her voice likewise drifted across the gorge, with an ethereal vibrancy. There were perhaps a dozen turns, and then silence. I listened, spellbound. And that brief exchange, that shouted conversation, with its unearthly sounds, the tension between the voices, the exhalations and long vowels echoing off the sides of the mountain, would haunt me for years, haunts me still.

They seemed to me to be speaking across time, that man and woman. Their ancestors, or other versions of themselves, had been having that conversation, exchanging those same sounds, that same music, across countless centuries. It was, for me, a lesson in both the durability and at the same time the fragility of our lives; that conversation, that calling across the chasm, represented a glimpse of eternity. And with this I am reminded that in ‘The History of Eternity’ Borges wrote of the idea of the infinite that it ‘liberates us, even if for only a few moments, from the unbearable oppression of the passage of time’. In the interview with Herbert Simon, Borges utters the phrase I asked you to bear in mind: ‘That’s the way I regard life. A continuous amazement. A continuous bifurcation of the labyrinth.’ Which in some way leads us back, in recursive fashion, to where we started, with Borges claiming that he could trace his first notion of the problem of infinity to that far distant biscuit tin.

But the moment passed, and continues to pass, lives on in my memory and imagination, and in so many memories that are the projections of myself out of the present, reminding us that of all the possible lives that each of us might live, we have this one, linked by an invisible thread to the innumerable lives that are unlived by us, but which – who knows – are even now being lived out by another version of ourselves in some other garden of forking paths. And having returned once more to that other, earlier life, I have ensured that this paper becomes an exercise in recursion in which I, the narrator, remember a previous self who wrote an article that recalls a stone cabin beneath a mountain where an even earlier version of that narrator discovers, for the first time, the stories of Jorge Luis Borges.

- In Borges, J.L., The Total Library: Non-Fiction 1922–1986, transl. Esther Allen (Penguin, 2001).

- Borges, J.L., ‘Prologue’ to Fictions, transl. Anthony Kerrigan (Calder, 1991).

- Corballis, Michael C., ‘The Uniqueness of Human Recursive Thinking’ in American Scientist, Vol 95 No. 3, 2007.

- Martínez, G., Borges and Mathematics, transl. Andrea G. Labinger (Purdue University Press, 2012).

- Primera Plana, ‘Borges–Simon, detrás del laberinto. Herbert Simon y Jorge Luis Borges’ IX, 414 (5 January 1971).

- Monegal, Emir Rodríguez, Jorge Luis Borges: A Literary Biography (Paragon House: 1988).

- Borges, J.L., ‘On Exactitude in Science’, Collected Fictions, transl. Andrew Hurley (Penguin, 1998).

- ‘When Fiction Lives in Fiction’ (ibid).

- ‘Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius’, transl. Alastair Reid, in Fictions (ibid).

- Monegal, Emir Rodríguez (ibid).

- ‘Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius’ (ibid).

- Helmenstine, Anne Marie, ‘What is a Wave Function?’ ThoughtCo, Jun. 25, 2024, thoughtco.com/defi>‘Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius’ (ibid).

- Peter Byrne, ‘The Many Worlds of Hugh Everett’, Scientific American (December 2007).

- Cited in the BBC documentary Parallel Worlds, Parallel Lives, dir. Louise Lockwood (2007).

- ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’ transl. Helen Temple and Ruthven Todd, in Fictions (1991).

- Everett, Hugh III, ‘Relative State Formulation of Quantum Mechanics’, Reviews of Modern Physics, Vol 29, No 3, 1957.

- Moran, Dominic, ‘Borges and the Multiverse: Some Further Thoughts’, in Bulletin of Spanish Studies, Vol 89, No 6, 2012.

- Rojo, Alberto J., ‘The Garden of the Forking Worlds: Borges and Quantum Mechanics’ Oakland Journal 9 (2005).

This article is taken from PN Review 281, Volume 51 Number 3, January - February 2025.