This article is taken from PN Review 279, Volume 51 Number 1, September - October 2024.

Pictures from the Rylands Library

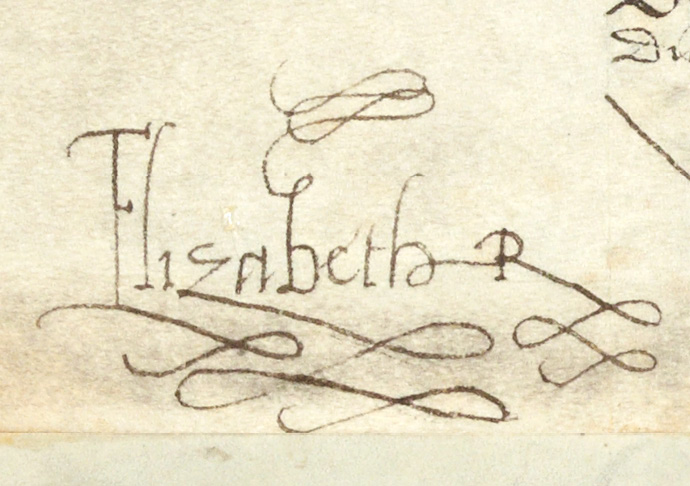

As Unique as a Fingerprint: Elizabeth I’s Signature

Covered by a scribe’s near impenetrable secretary hand, this roll gives the account of the New Year gifts received and presented by Elizabeth I in 1559. Her iconic (in all senses of the word) signature, a relatively newfangled warrant of authenticity, appears four times on the document’s surface.

Involving all echelons of court culture from the nobility down to their highnesses’ dustmen (Henry Sullivan), these gifts were carefully ‘adjusted to the rank, standing and wealth of donors and recipients’ (Patrick Collinson). The ritual reached its zenith during the purported Golden Age of Gloriana’s reign, before becoming obsolete with the demise of Charles I.

Though joking with Fénelon, the French Ambassador, that she liked to ‘take with both hands and give with her little finger’, Elizabeth’s motives for prizing this custom were not exclusively acquisitive. As a child she had seen how the ritual giving of gifts at New Year placated bad feelings, ameliorated offences and reinforced kinship ties amongst the members of her scheming, belligerent Tudor family (Valerie Schutte). As a daughter relegated far down the pecking order behind a younger brother and older sister, she knew only too well that if the gifts she gave were chosen wisely she could use them for political advantage to bolster her position at court (Lisa Klein).

So in the New Year of 1544, finding herself in the perilous position of being at odds with her tyrant father, she devised a stratagem to use her gift for her stepmother, Katherine Parr, as the means of repairing the rift. Though only eleven years old she translated Marguerite de Navarre’s poem ‘The Glass of the Sinful Soul’ from French into English, transcribing the complete text in the ‘elegant italic hand which she was well on the way to mastering’ (Patrick Collinson) and designed and stitched the book’s embroidered binding (by all accounts) herself. Moved by the performance of loyalty to her family encoded in this gift (Valerie Schutte), the stepmother interceded, and the father warmed again to his third child.

If, after all, ‘to give something is to give a part of oneself’ (Marcel Mauss), what is the nature of a gift crafted by hand and in one’s hand? For despite the ‘emergence of generations of writing machines’ we continue to believe that ‘true subjectivity is physically inscribed in the movement and pressure of the pen on paper (or as here, vellum), leaving an unexchangeable personal trace whose aura resides precisely in its material authenticity’ (Sonya Neef).

Elizabeth sought to demonstrate her pedigree as a princess of the blood, and a chip off the old block, through the penning of the knots and serifs of her autograph hand cloned from that of her father’s. As if it were a sequence of DNA, she deployed her handwriting to lay claim to her Tudor identity. For as the ‘sloughed fragments of a corporeal self’ (Hunter Dukes), her writing, and especially her signature, acts as ‘a sign almost as unique as [her] fingerprints’ (Neef).

Elizabeth I’s New Year’s Gifts, English Manuscript 117, 1559 (Image provided by The John Rylands Research Institute and Library, © The University of Manchester, 2024)

This article is taken from PN Review 279, Volume 51 Number 1, September - October 2024.