This article is taken from PN Review 286, Volume 52 Number 2, November - December 2025.

Pictures from a Library

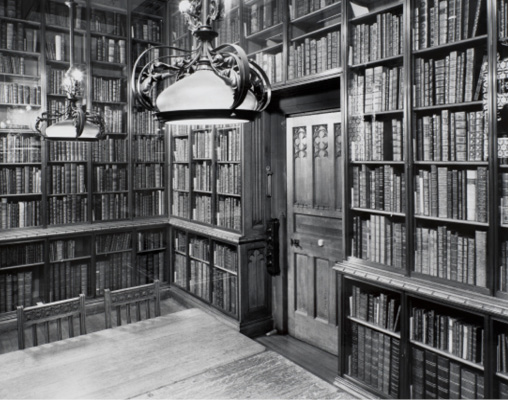

Enlightenment in the John Rylands Library

When Enriqueta Rylands bought the Spencer Collection of books in 1892, it caused something of a stir. Reports in the press held out the hope that while the purchase of such a ‘magnificent collection’ had been established, the gift of it to that ‘dirty, uncomfortable city Manchester’ had not, and would never be confirmed. ‘What’, railed the newspapers, ‘do unsavoury… and uncultivated boors want with a library, and such a one?’ Especially as ‘they have not enough light to read by and the books they already have are wretchedly kept’.

Enriqueta’s riposte to these slurs is perhaps best inferred from her deeds rather than her words. Not only did she choose to wilfully give her books (including those formerly part of the Spencer Collection) to the people of Manchester, she also sought to house them in the setting of the magnificent neo-Gothic library she built in their city’s heart. Moreover, as seen in the photograph shown here of the Rylands’ Early Printed Books Room, she displayed her incunabula in the finest of glass-fronted Polish oak bookcases, where their arrangement conformed to Proctor order, denoting the highest standards of rare book librarianship and bibliography at the time.

Furthermore, she ensured they were illuminated by the ‘lucent beauty’ (Graham Gooday) of the medium of electricity, which was transmitted via exquisitely crafted chandeliers fashioned to perfection in glass, gun metal and bronze in the workshop of J.W. Singers of Frome and operated by the twist of a wrist. So their new Mancunian home was one of the first public buildings in the city to be lit by electric lighting, sparing readers and staff alike ‘the hunched, squinting nocturnal deportment that generated headaches, eye strain and back ache’ and the ‘notoriously malodorous stench’ of gas and candle. Instead they were afforded the luxury of working in an ‘environment conducive to scholarly concentration’ (Chris Otter).

Wary of the hazard of conflagration, Enriqueta’s preference for a light ‘without flames or sparks’ (Jane Bronx) was also rooted in her belief that electricity would keep the Rylands safe from fire. Presumably oblivious to the fate, less than a decade earlier, of J.P. Morgan’s ‘vast and splendiferous’ (Artistic Houses) library in his New York home which was ‘ruined’ (Jill Jonnes) by a dodgy lamp fitted by Thomas Edison’s Electric Light Company, she trusted in electricity’s capacity to preserve both books and eyesight alike.

Yet, practical issues aside, the qualities of electric lighting do not end here, for early adopters of this new technology (like Enriqueta) were also keenly aware of its symbolic properties as a medium that could literally and mentally enlighten (Richard Leahy). Such penetrative radiance banished not only the darkness of night but also that of ignorance, for light represents ‘rationality and knowledge’ (Greg Lynall). And nowhere is this more evident than in a library where books exert their power to illuminate the mind and engender learning, especially in places prejudicially (and erroneously) dismissed as ‘dirty and uncomfortable’.

Image provided by and © of The John Rylands Research Institute and Library, The University of Manchester

This article is taken from PN Review 286, Volume 52 Number 2, November - December 2025.